‘Beauty is the perfection, which like infinity, we try to meet but never succeed in doing. … I put that which enriches my life and endows it with wonder and meaning here beside me in my home where it is visible in order that each day may be filled to the brim with beauty.'

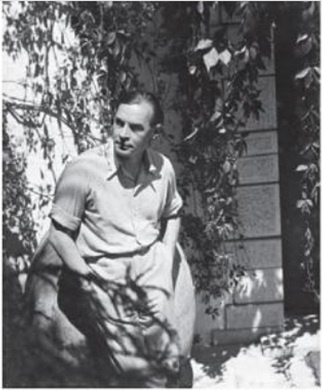

Erich Maria Remarque

For Remarque, art was an indicator of mankind’s progress, of humanistic values. He viewed it as a weapon against, and antidote to barbarism, persecution, dictatorship, and menace of war.

World fame and the beginning of an art collector

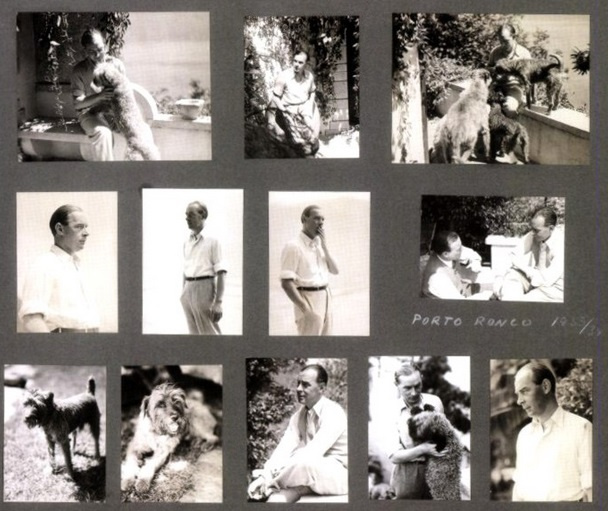

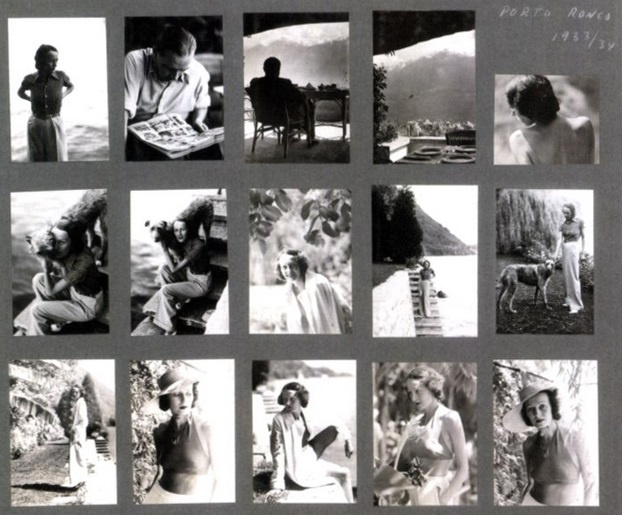

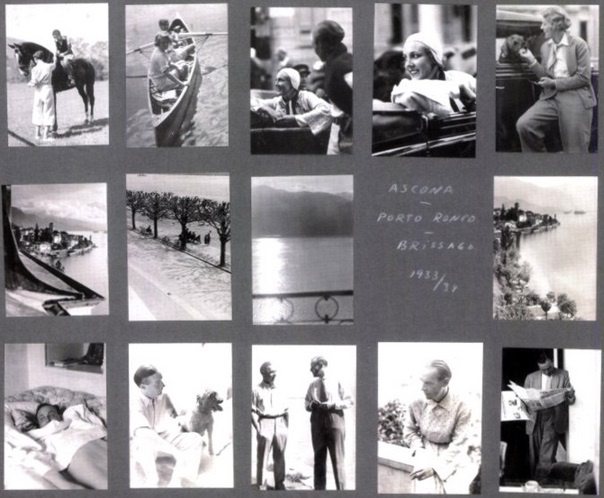

In 1928, ten years after World War I was over, Remarque, to rid himself of demons of war haunting him, wrote the novel All Quiet on the Western Front. The book made him world-famous. Money from royalties and film rights started flowing in.Having woken up this rich, Remarque decided to invest the money into shares, gold, and real estate, and his new romantic companion Ruth Albu advised him to purchase artworks. Ruth, an actress in Berlin and an art collector’s daughter, was quite knowledgeable about antiquities. When Remarque, in 1931, bought a villa at Lake Maggiore, in Porto Ronco, Switzerland, she helped him in decorating the interiors.

Soon, the writer’s house filled with elegant antiques that revealed their owner’s aesthetic preferences. Bronze statuettes, vases by old Egyptian, Chinese, and Greek ceramists, rococo furniture, 17th-century Persian carpets, Venetian glass — all these wonderful pieces made by masters of ages past and gone assuaged the anxiety of the writer’s heart. Enthusiastically, he plunged into art history buying dozens of books. As time passed, the research work of his own, meeting art dealers, visiting museums, and studying his collection would make Remarque not only a perceptive connoisseur of art, but an erudite collector and expert as well.

Erich Maria Remarque. Shadows in Paradise.

When Ross came to America, he got hired by the prominent New York art dealer and collector Silvers. His new assistant’s knowledge allowed Silvers to often introduce Ross to his clients as a curator of the Louvre. ‘During my stay in the Brussels Museum I had learned one thing: that objects begin to speak only after you have looked at them for a long time, and that the ones that speak soonest are never the best. <…> In this way I gradually learned the feel of patinas. On summer evenings I would peer into the cases for hours, and so became a good judge of texture, though I had never seen the colours by proper daylight. But, above all, my studies in the dark had in course of time given me a blind man’s heightened sense of touch.'

‘The bronze had had the right feel in the shop; the contours and reliefs were sharp, which may have been the reason for the museum expert’s opinion, but to me they did not seem new. When I closed my eyes and felt them slowly and carefully, I became more and more convinced that the piece was very old.

I had seen a similar bronze in Brussels. At first the curator had taken it for a Tang or Ming copy. The Chinese had begun long ago — as early as the Han dynasty at the beginning of our era — to bury copies of Shang and Chou bronzes; the patina on these pieces was just about perfect, and it was very hard to identify them unless there were slight mistakes in the ornaments or defects in the casting.'

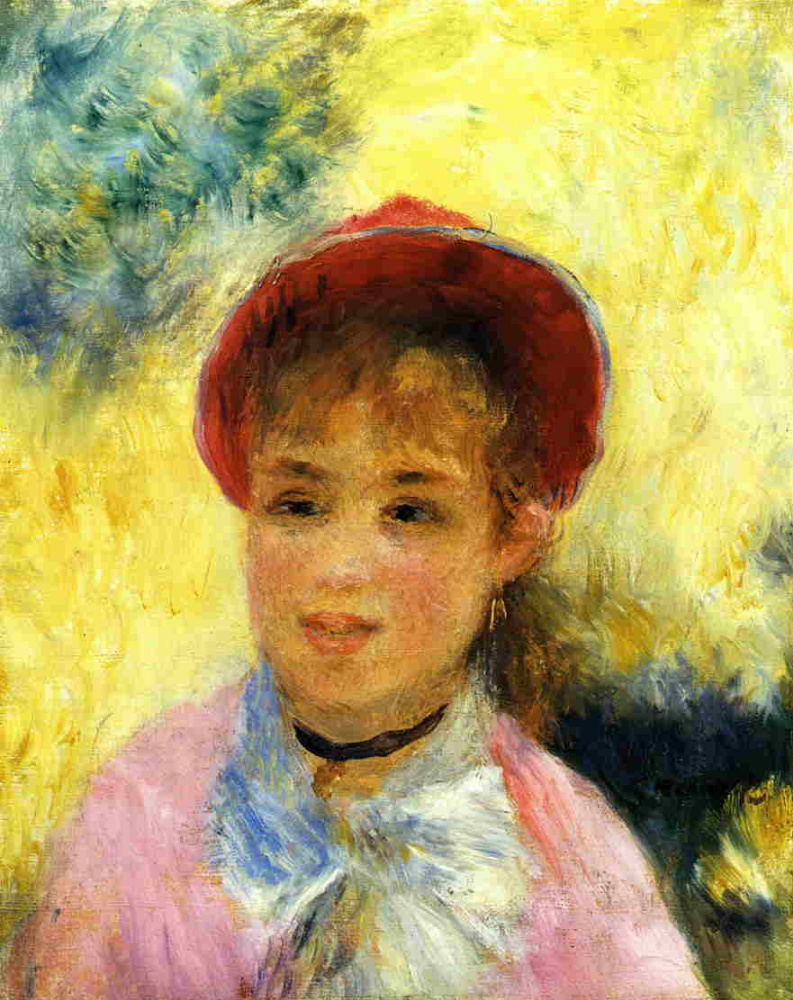

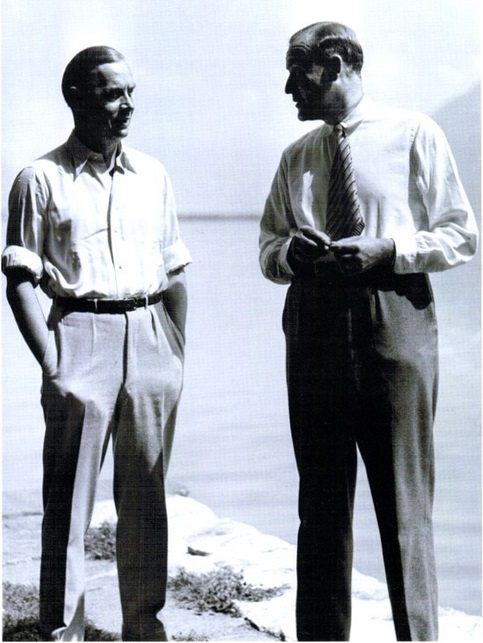

Two comrades: ‘Boni und Feilchen’

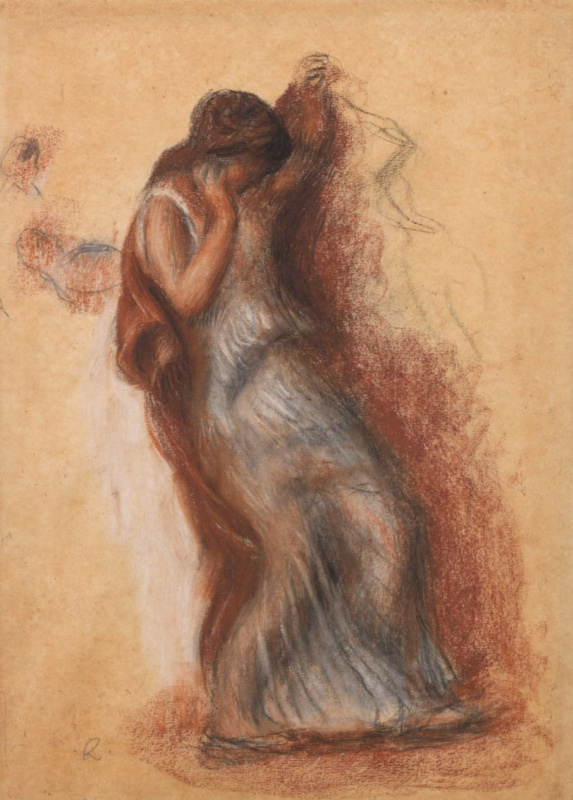

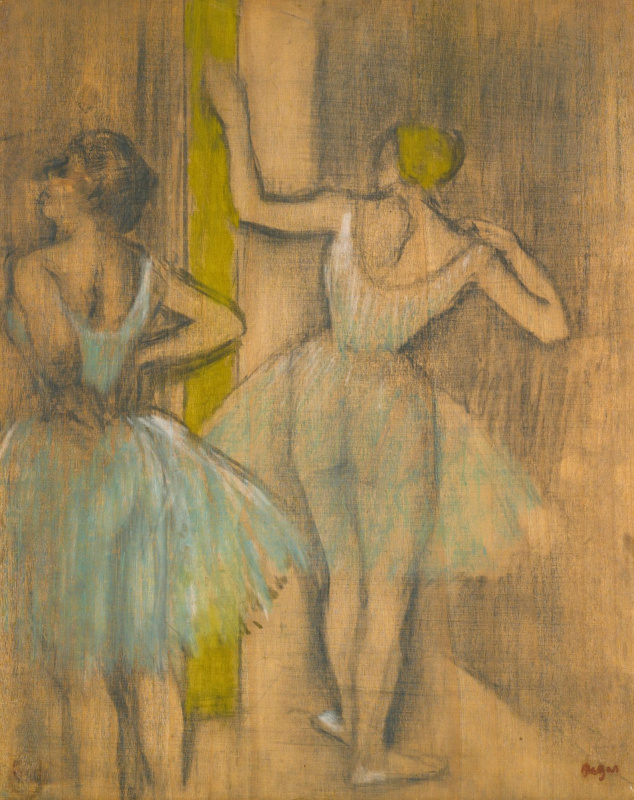

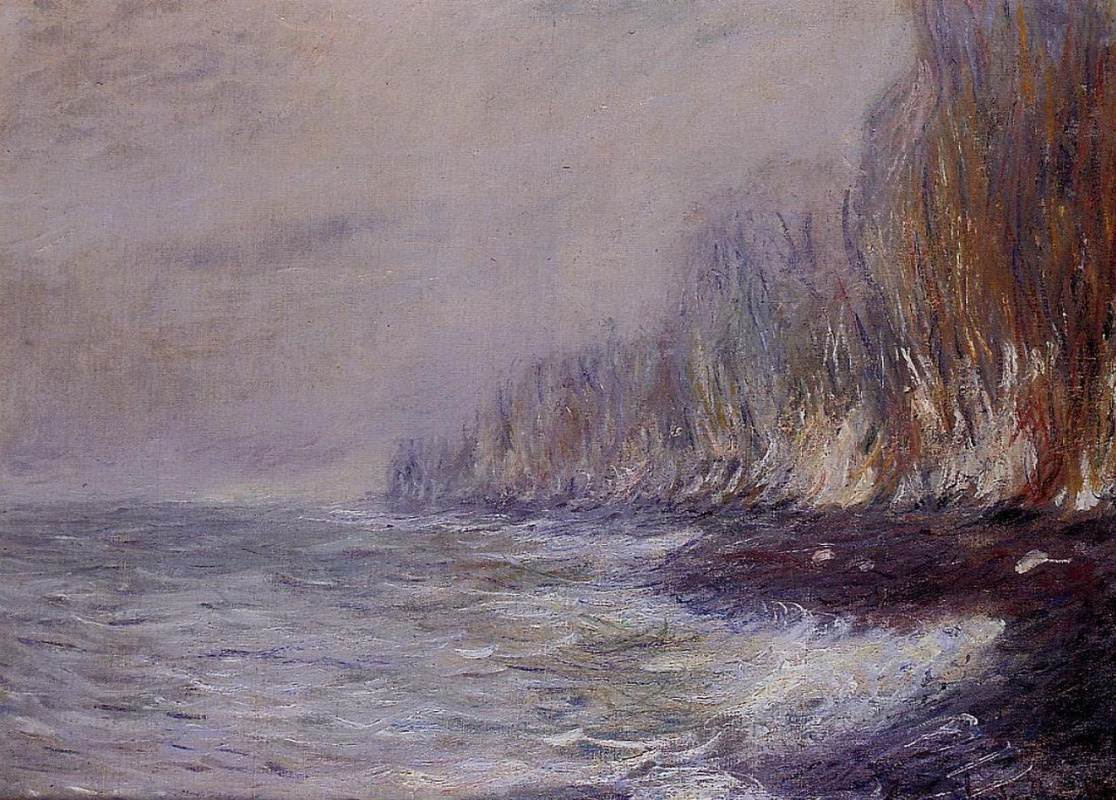

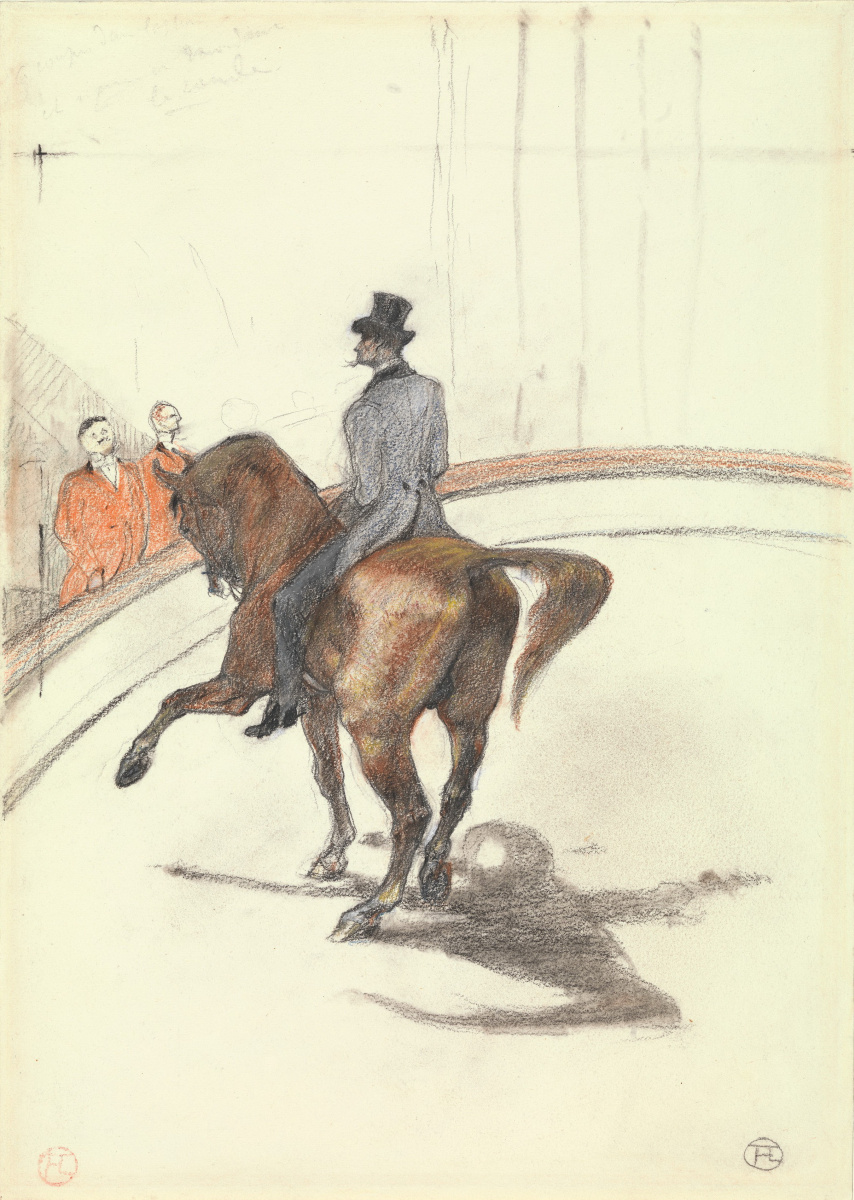

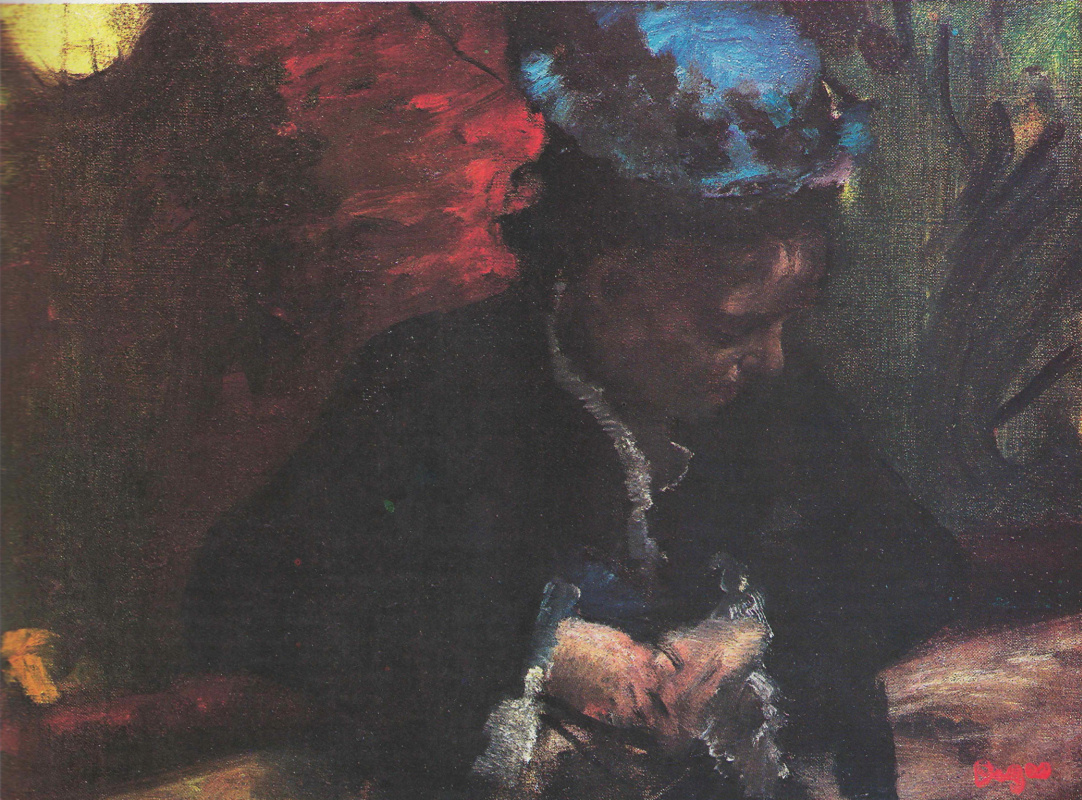

In 1930, Ruth Albu introduced Remarque to Walter Feilchenfeldt, a leading expert in Modernist painting in Europe. His was a crucial role in the progressive transformation of the amount of art objects amassed by Remarque into one of the best private collections of that time. In his turn, the writer, who possessed a fabulous fortune, became a very important client for the art dealer in the years of the Great Depression in Germany. As time passed, a true, long-lasting friendship developed from their affinity and their mutual interest in art where Walter was Remarque’s teacher as well as his expert. Remarque addressed the gallerist with the friendly name of Feilchen, and Walter, like Remarque’s other friends, called him Boni.Remarque was passionate about Impressionist art and bought from Walter works by Monet, Pissarro, Degas, Cézanne, and Renoir. One of his first purchases was Degas’s pastel drawing Three Dancers.

A high-calibre professional, Feilchenfeldt had to work without legal rights and in constant fear of deportation, and quite a number of the episodes of his vagrancy can be found in Remarque’s novels Arch of Triumph and Flotsam (titled in German Liebe deinen Nächsten — Love Thy Neighbour).

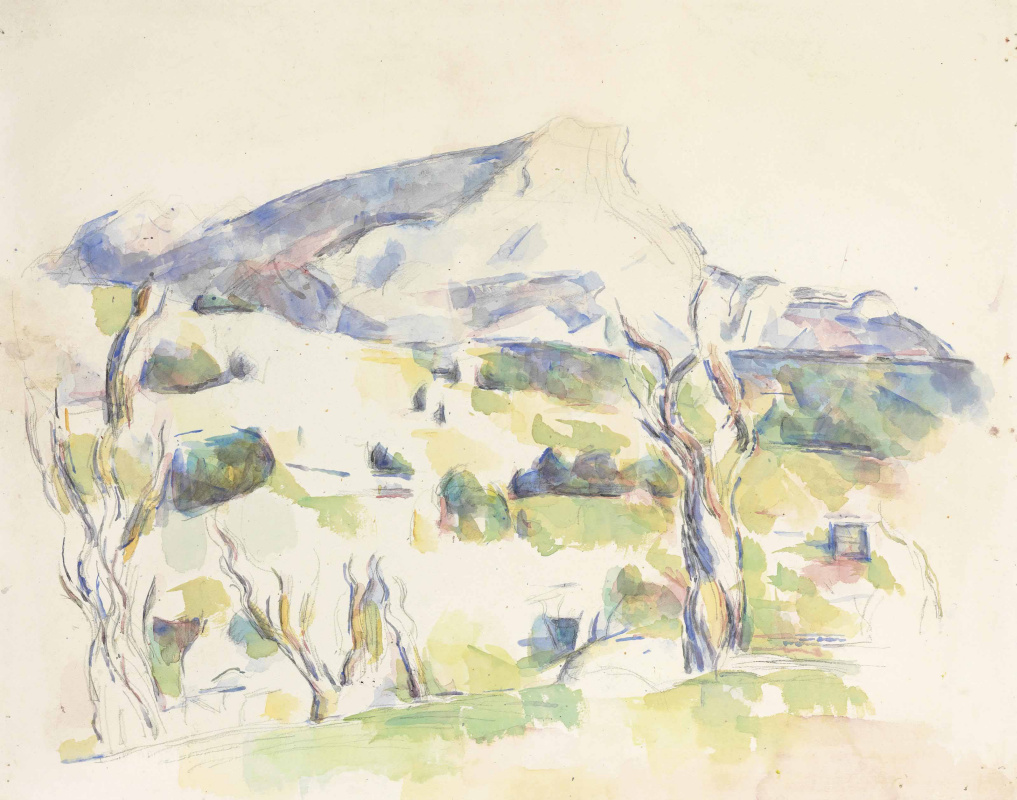

Remarque became the godfather of Walter Feilchenfeldt’s son. As the Feilchenfeldts' family legend has it, Remarque only agreed to be the godfather on condition that the boy was named after him. But the parents detested the name Erich and used the writer’s middle name. So Feilchen’s son was called Walter Maria Feilchenfeldt. Today, this Walter Feilchenfeldt is well-known as an expert in Van Gogh and Cézanne, the author of monographs about these artists and catalogues of their works, and one of the creators of the online catalogue raisonné of Paul Cézanne's paintings. Besides, he published the work Boni and Feilchen. The Collector and His Dealer, that was then included, as a chapter, into the book Remarque’s Impressionists: Art Collecting and Art Dealing in Exile.

Later, the writer had an opportunity to take part in a project aimed at the preservation of his favourite painter’s artistic legacy. Remarque was one of those who sponsored the Cézanne Memorial Committee founded in 1952 that would buy out Paul Cézanne's studio in Aix-en-Provence. In 1954, the house was turned into the painter’s museum, L’atelier Cézanne.

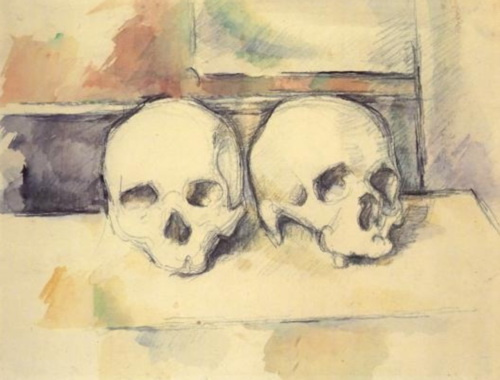

Paul Cézanne. Still Life with Two Skulls. 1890. Photo from: strannik17.livejournal.com

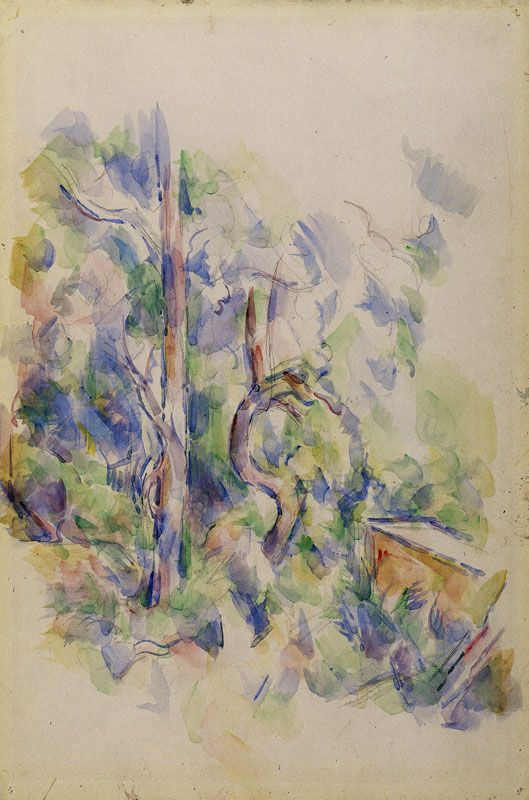

In 1939, Remarque, through Walter’s mediation, bought his first Cézanne, the large canvas Dans la plaine de Bellevue (On the Plain of Bellevue). As though Walter felt that was the last deal they were engaged in together, he gave Remarque, as a present, Cézanne's water-colour Still Life with Two Skulls, and jokingly called it their companion portrait. Shortly afterwards, war would separate them for years, and Remarque would frequently write letters to him whom he called the only friend of his young years.

Remarque, Dietrich, Cézanne. Which one is the ‘third-person-out’?

In 1939, at the Venice Film Festival, Remarque met Marlene Dietrich. She, a goddess among film stars, and he, an individualistic intellectual — they seemed to be poles apart. However, they had a lot in common: they both early achieved success, were financially independent, and each of them, some time before, had demonstrated in public their disgust at the Nazis although neither of them was a Jew; then they both emigrated to America; and each had gone through a personal crisis before the war. Remarque wrote in his letter to the actress, ‘We have much too much past and no future in sight.'Some details of their affair Remarque would later describe in the novel Arch of Triumph.

Marlene Dietrich in her New York apartment. 1948. Photo from: lumieregallery.net

Remarque was completely obsessed by Dietrich. The actress’s fickleness and coldness of manner tortured him, he was jealous of her admirers and lovers who were still there even after he came into her life. The writer’s salvation, in the periods of agonies, depression, and jealousy, were new acquisitions for his collection — and Cézanne's water-colours comforted him more than ever.

Well, the only thing beyond Marlene’s control was the writer’s collection, the passion with which he pursued his hobby. So Cézanne's above all? OK — and Dietrich now and then demanded the French artist’s paintings to be given to her as a proof of the writer’s love. Remarque readily lavished elegant jewellery on his woman, and gave her works by Corot, Cézanne, and Delacroix (she herself owned several landscape paintings by Corot and Utrillo).

The Promised Land

Right before the war, in September, 1939, Remarque came to America and settled in Los Angeles. His first year in the United States was hard: though financially independent, he remained lonely and depressed after his displacement. Art and collecting artworks became an essential part of his life in emigration.At that time, there were no big museums and galleries in Los Angeles. When in 1940, Sam Salz, an art dealer and a refugee, opened there an affiliated branch of his gallery, Remarque was one of the first to visit it. Ironically, Salz was Feilchenfeldt’s sworn enemy, but Remarque again became a lifeline for Salz and introduced him to Hollywood actors and producers.

Salz did his best to find Cézannes for Remarque, but he drew the writer’s attention to other Modernists, too. Remarque’s collection widened as it included the works by artists that were new to him: Toulouse-Lautrec, Utrillo, Picasso, Daumier, and Pissarro.

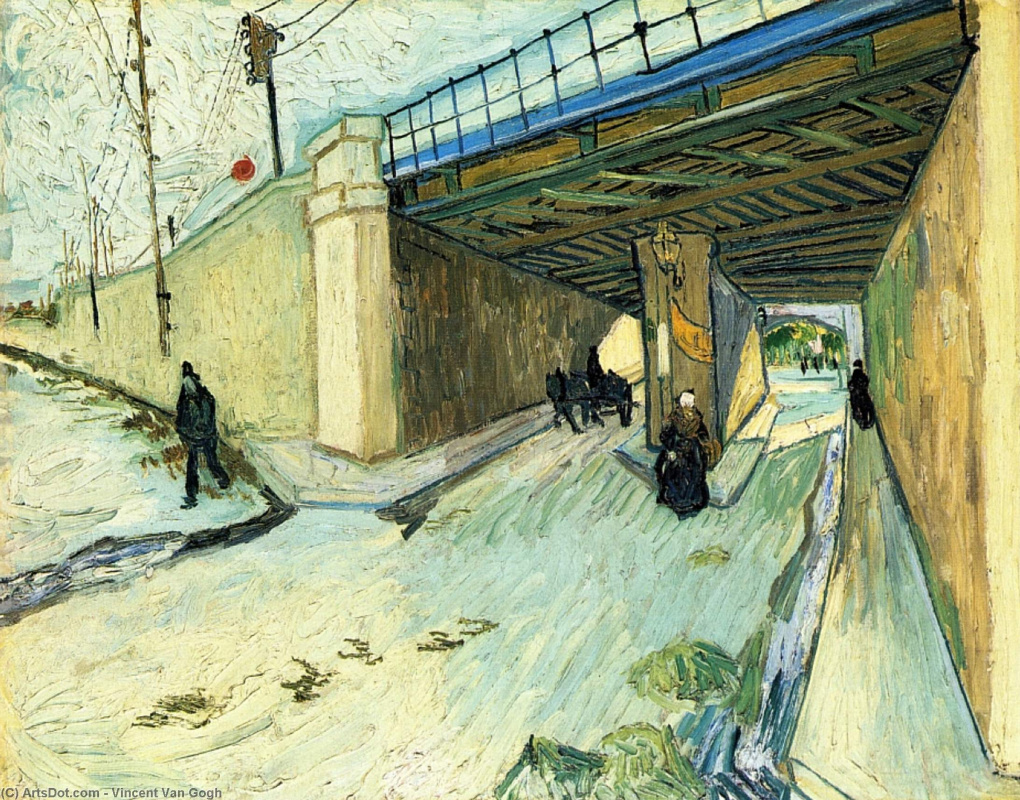

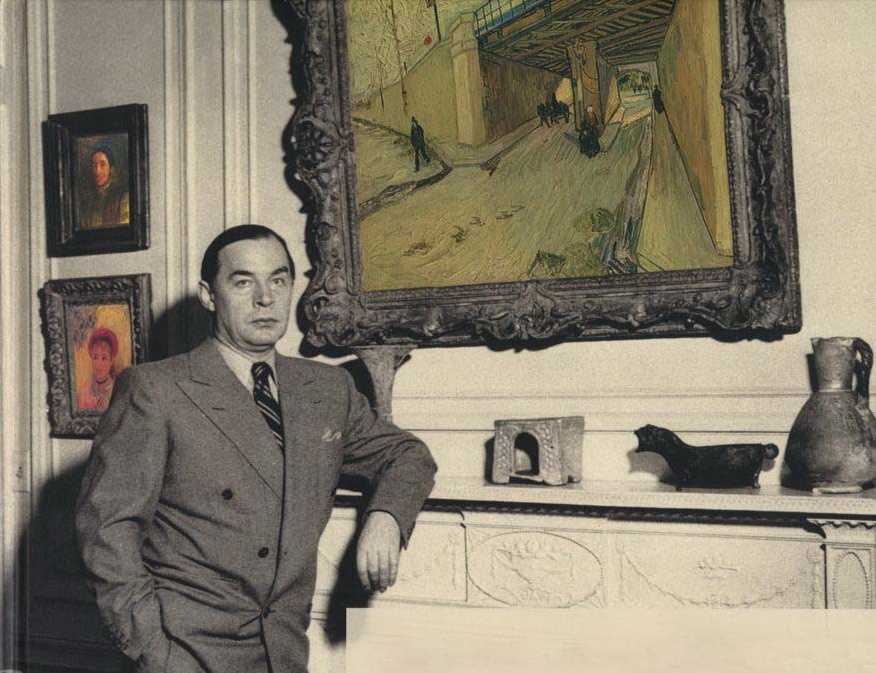

In the summer of 1940, Remarque changed his old attitudes to art collecting. Usually, only his friends had been allowed to see his collection — now he wanted to share it with the public. In February 1941, the writer loaned four items to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the French Painting from David to Toulouse-Lautrec exhibition, and in January 1942, his Van Gogh went to an exhibition at the Rosenberg Gallery, New York.

On making a close acquaintance with Roland McKinney, the director of the Los Angeles County Museum, Remarque loaned his entire collection there to be presented as the E. M. R. Collection at the exhibition held from November 1942 to July 1943. It was a prominent event for the city, and it did not go unnoticed.

In 1943, at the Knoedler Galleries, there was another exhibition of Remarque’s collection featuring thirteen paintings, 32 works on paper, and two Fayum mummy portraits. The New York Times critic Edward Alden Jewell wrote that the Remarque Collection played ‘an uncommonly large role' in the art season. After the Knoedler show, most of the items of the Remarque collection went to an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and later, they were sent to the Kunsthaus Zurich.

His works by Cézanne Remarque loaned to the Metropolitan Museum, where they stayed from 1949 to 1956, and then, until 1979, they were on display in the Kunsthaus Zurich.

Remarque’s collection included two Fayum mummy portraits, rare examples of Ancient Egyptian art of the Roman era. In the early 20th century, they belonged to Rudolf Mosse, a German publisher of Jewish origin, who owned a most extensive art collection. He died in 1920 and left everything to his daughter Felicia Lachmann-Mosse. The Nazis expropriated the collection, of which more than 400 items were then sold at an auction in 1934. It remains obscure when and where Remarque got these portraits, as he never purchased artworks of dubious provenance. In the 1970s, the Kunsthaus Zurich bought the Fayum portraits at an auction, and in 2015, it restituted them to the Mosse family’s heirs.

Mount of happiness

In 1948, Remarque returned to his villa Casa Monte Tabor in Switzerland. In the 1930s, it had been his stronghold where to retreat from the Nazis, and now it was his paradise where he would live with his second wife, the Hollywood actress Paulette Goddard. For both of them, it would be their last and happiest marriage. Paulette helped him feel the joy of life again, his melancholy could not resist the actress’s sunny, easy disposition. They travelled about Europe a lot, visiting, one by one, St. Moritz, Salzburg, Vienna, London, Paris, Cannes, Venice, and Paulette’s favourite city of Rome.They both loved art. Long before she met Remarque, Paulette had collected art objects, too. She was into antique furniture, Ancient Egyptian and Asian applied art, and pre-Columbian cultures. In 1947, she and her third husband Burgess Meredith had opened an antique shop and the High Tor Associates gallery in the state of New York.

Paulette Goddard. Photo from: the-decophile.blogspot.com

Besides, the actress had a superb collection of Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Trabert & Hoeffer-Mauboussin, and Paul Flato jewellery and exclusive decorations designed by Salvador Dalí. Paulette Goddard never bought jewellery, but all her husbands and admirers were well aware what exactly she would be delighted with. When she was not cast as Scarlett in Gone with the Wind, the two presents became a consolation to her: a diamond brooch from Jock Whitney, an investor of the film, and a set of a pair of earrings and a bracelet from her second husband Charlie Chaplin.

She was living in the San Angel Inn across from his studio. She chanced to learn that the police were preparing to arrest him, and she warned the painter. Helped by her, he crossed the border, came to California, and told the reporters who were meeting him that Paulette had saved his life. In the years 1940—1941, Rivera painted the actress’s portrait. He started it in Mexico and finished in America.

Paulette Goddard outlived her husband by twenty years. She bequeathed $ 20,000,000 to New York University (NYU) for the development of educational and research programmes. To accomplish her will, in 1995, the university created the Remarque Institute. The main goal of its numerous projects is supporting and promoting the ties between Europe and America. This is what Remarque wished himself.

Text by: Irina Olih