Aivazovsky and sausages, Van Gogh and geranium, Klein and gold bars… ARTHIVE flashes back to some artists' professional fees that were too curious and offbeat even by standards of such a bizarre, unpredictable, and hardly explicable phenomenon as the art market.

Ivan Aivazovsky

In 1840, Aivazovsky came to Italy and had a tremendous success. Rome met a fresh graduate from the Academy of Fine Arts with cheers and applause. The Art Gazette wrote, ‘Gaivazovsky's pictures in Rome are judged the best in the exhibition. <…> the newspapers have sung his praises loudly and all are unanimous that only Gaivazovsky is able to depict light, air and water so truly and convincingly.'

In 1840, Aivazovsky came to Italy and had a tremendous success. Rome met a fresh graduate from the Academy of Fine Arts with cheers and applause. The Art Gazette wrote, ‘Gaivazovsky's pictures in Rome are judged the best in the exhibition. <…> the newspapers have sung his praises loudly and all are unanimous that only Gaivazovsky is able to depict light, air and water so truly and convincingly.'

Chaos. The creation of the world

1841, 106×75 cm

His canvas Chaos. The Genesis was purchased by Pope Gregory XVI. There is another theory, though, that Aivazovsky rejected the money and the piece was his gift to the pontiff. In either event, the deed was done: what was good for the Pope, was good enough for any Italian. Aivazovsky’s pictures were wildly sought after by local noblemen, and commoners had but to content themselves with imitations and copies — a seascape in Aivazovsky’s style could be found in every smallest shop. However, neither the national-wide popularity, nor the Pope’s attention, nor the eulogies William Turner dedicated to him swelled Aivazovsky’s head.

Once in Venice, he met a marquess, who offered him some sausage as a fee. Aivazovsky did not say no.

Of course, this agreement was something quite different from some heart-rending episodes from the biographies of Amedeo Modigliani or Niko Pirosmani, who did have to work for food. Aivazovsky was a real gourmet, and the food in question was actually a great delicacy — it was first-rate Italian salami manufactured by the Venetian nobleman’s brother. Still, sausage is but sausage.

That was just like Aivazovsky. However high the wave of the public admiration raised him, however tempestuous the sea of his worshippers was, he always had both feet on the ground. In his nature, sublime poetry went hand in hand with pragmatic prose. Chekhov, on meeting Aivazovsky, did have reasons to write, ‘In him alone there are combined a general, a bishop, an artist, an Armenian, a naive old peasant, and an Othello.'

Once in Venice, he met a marquess, who offered him some sausage as a fee. Aivazovsky did not say no.

Of course, this agreement was something quite different from some heart-rending episodes from the biographies of Amedeo Modigliani or Niko Pirosmani, who did have to work for food. Aivazovsky was a real gourmet, and the food in question was actually a great delicacy — it was first-rate Italian salami manufactured by the Venetian nobleman’s brother. Still, sausage is but sausage.

That was just like Aivazovsky. However high the wave of the public admiration raised him, however tempestuous the sea of his worshippers was, he always had both feet on the ground. In his nature, sublime poetry went hand in hand with pragmatic prose. Chekhov, on meeting Aivazovsky, did have reasons to write, ‘In him alone there are combined a general, a bishop, an artist, an Armenian, a naive old peasant, and an Othello.'

Portrait of Pyotr Kapitsa and Nikolay Semyonov

1921, 71×71 cm

Boris Kustodiev

Once, two youths barged in to Kustodiev’s studio. Scarcely had they been inside when they demanded that the artist set aside all other issues. The young people wanted him, a most celebrated Russian portrait painter, who had portrayed Russian emperors, tsesareviches, and pop stars of those days, to paint a companion portrait of them right away. They were not celebrities then, but they assured Boris Kustodiev they were sure to become ones soon.

‘And so bushy-browed and ruddy-faced were they, so assertive and cheerful that I had but to agree,' Kustodiev later confessed to his friend Feodor Chaliapin. The visitors (they were the future academicians Pyotr Kapitsa and Nikolay Semyonov) would do what they promised Kustodiev: later, they both would become Nobel Prize winners.

Those were the hard, dark days of the year 1921. By that time, Kustodiev had lost faith in the Bolsheviks. He had to collaborate with them, though. He was a member of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, and designed theatrical productions (ideologically correct ones, of course), drew agitprop posters and popular prints. His wife Julia contributed to the family’s budget by cutting firewood on Sundays — and got some firewood as the pay. Kustodiev himself was in no physical condition to do any jobs on the side: after a spinal surgery, he could hardly move his legs. Despite all that, he never lost hope and sense of humour. And he was disarmed by his young commissioners' optimism and confidence that everything would somehow be all right.

Of course, the pay they offered did play a role in his consent to paint a portrait of them. Kapitsa and Semyonov paid with a cockerel and a sack of millet they had earned for fixing somebody’s mill. By then standards, it was a fee quite decent both for the future Nobel Prize winners and for one of Russia’s most celebrated portrait-painters.

Once, two youths barged in to Kustodiev’s studio. Scarcely had they been inside when they demanded that the artist set aside all other issues. The young people wanted him, a most celebrated Russian portrait painter, who had portrayed Russian emperors, tsesareviches, and pop stars of those days, to paint a companion portrait of them right away. They were not celebrities then, but they assured Boris Kustodiev they were sure to become ones soon.

‘And so bushy-browed and ruddy-faced were they, so assertive and cheerful that I had but to agree,' Kustodiev later confessed to his friend Feodor Chaliapin. The visitors (they were the future academicians Pyotr Kapitsa and Nikolay Semyonov) would do what they promised Kustodiev: later, they both would become Nobel Prize winners.

Those were the hard, dark days of the year 1921. By that time, Kustodiev had lost faith in the Bolsheviks. He had to collaborate with them, though. He was a member of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, and designed theatrical productions (ideologically correct ones, of course), drew agitprop posters and popular prints. His wife Julia contributed to the family’s budget by cutting firewood on Sundays — and got some firewood as the pay. Kustodiev himself was in no physical condition to do any jobs on the side: after a spinal surgery, he could hardly move his legs. Despite all that, he never lost hope and sense of humour. And he was disarmed by his young commissioners' optimism and confidence that everything would somehow be all right.

Of course, the pay they offered did play a role in his consent to paint a portrait of them. Kapitsa and Semyonov paid with a cockerel and a sack of millet they had earned for fixing somebody’s mill. By then standards, it was a fee quite decent both for the future Nobel Prize winners and for one of Russia’s most celebrated portrait-painters.

Yves Klein’s Leap into the Void (1960, photo by: Harry Shunk, János (Jean) Kender)

Yves Klein

The French artist Yves Klein was an enthusiastic inventor of amusements and a tireless adventurer, an Indiana Jones sort of painter. He invented anthropometries (pictures created by pressing a human body to the canvas — 1, 2, 3) and a specific blue colour he registered as International Klein Blue (IKB). He used to tie his pictures to his car’s roof and drive from Paris down to the country, exposing the canvases to rain, wind, dust — thus making the natural elements his colleagues and co-creators. He would use a gas burner instead of a paintbrush, and he would cause his pictures to move by means of electric motors. There were times when he made his pictures from wafer-thin gold leaves that woke to life and started rustling at a slightest motion of air.

However, in Klein’s artistic activity, there was a period literally golden — when the buyers paid him in gold bullions (it was a sine qua non of the agreement). Interestingly, in exchange for the gold, Klein offered his buyers empty spaces. Even more interestingly, empty spaces turned out to be the most saleable articles. Neither the gas-burnt sooty canvases, nor the opuses produced with naked beauties' bodies covered in paint were as popular, — Klein’s principal way of earning his living was judo coaching.

The empty spaces business was a highly ritualised ceremony. Some of the gold received from his customers (who were often quite reasonable people, like Albert Camus) Klein, in their presence, threw into the Seine, as a symbolic tribute to the Void.

Definitely, the idea of the painter’s gesture being more important than painting as such was not something everyone welcomed with cheers. Yves Klein’s place in art history is still a point of controversy. Some believe that Klein was the one to most perfectly understand, formulate, and turn into cash the very essence of modern art. Others think he was an excellent swindler. There are those, too, who are quite right saying that one explanation does not make the other impossible.

The French artist Yves Klein was an enthusiastic inventor of amusements and a tireless adventurer, an Indiana Jones sort of painter. He invented anthropometries (pictures created by pressing a human body to the canvas — 1, 2, 3) and a specific blue colour he registered as International Klein Blue (IKB). He used to tie his pictures to his car’s roof and drive from Paris down to the country, exposing the canvases to rain, wind, dust — thus making the natural elements his colleagues and co-creators. He would use a gas burner instead of a paintbrush, and he would cause his pictures to move by means of electric motors. There were times when he made his pictures from wafer-thin gold leaves that woke to life and started rustling at a slightest motion of air.

However, in Klein’s artistic activity, there was a period literally golden — when the buyers paid him in gold bullions (it was a sine qua non of the agreement). Interestingly, in exchange for the gold, Klein offered his buyers empty spaces. Even more interestingly, empty spaces turned out to be the most saleable articles. Neither the gas-burnt sooty canvases, nor the opuses produced with naked beauties' bodies covered in paint were as popular, — Klein’s principal way of earning his living was judo coaching.

The empty spaces business was a highly ritualised ceremony. Some of the gold received from his customers (who were often quite reasonable people, like Albert Camus) Klein, in their presence, threw into the Seine, as a symbolic tribute to the Void.

Definitely, the idea of the painter’s gesture being more important than painting as such was not something everyone welcomed with cheers. Yves Klein’s place in art history is still a point of controversy. Some believe that Klein was the one to most perfectly understand, formulate, and turn into cash the very essence of modern art. Others think he was an excellent swindler. There are those, too, who are quite right saying that one explanation does not make the other impossible.

Night cafe

September 1888, 72.4×92.1 cm

Vincent Van Gogh

Van Gogh’s fees were different in different periods of his life and work, ranging from little to next to nothing. In 1882, he boasted (in a letter to his brother Theo) that he had succeeded in selling a painting of his — ‘… the first sheep has crossed the bridge.' But more often than not, he had to make do with bartering. At the start of his career, he usually paid his models with what he had painted. He tried hard to talk them into sitting nude for him — no doubt, he hoped for something more in the end, as the models he looked for, mostly girls of the port, were of quite loose morals. However, even the whores of Antwerp turned him down. It is hard to tell for sure what repelled the models more — the painter’s disagreeable and erratic nature or his artistic manner. Van Gogh never flattered a model and normally rendered likeness but very roughly, and the tints prevailing in his palette were depressive grey and brown.

Anyway, the only reward he occasionally received in those years was someone’s consent to sit for him. Later, in Paris, he met Agostina Segatori who ran the Café du Tambourin. Agostina, who herself ranked it as a museum rather than a café, agreed to take Van Gogh’s paintings as the price of food. She even frequently sent him flowers — not to express her admiration, though, but because she wanted the pictures she got from him to be more brightly coloured.

One of Van Gogh’s most celebrated paintings, The Night Café created in Arles became, too, his rent payment. The artist, who was then lodging in a room on the first floor, was in debt to the landlord. Vincent offered him, who ‘had taken so much of his money,' to paint his place, and the café owner had but to agree.

The room, normally crowded, has become almost empty in a flash (it was typical when Vincent would adjust his easel). We can see the unfinished glasses of wine, the carom billiards table left by the players, the tramps in the corners who have nowhere to escape and who are trying to hide their faces… The owner is the only one who is standing up and posing — as intrepid as one who has nothing to lose.

It turned out to be first-rate publicity. The Night Café made history as a visual meme symbolising loneliness, desolation, despair. Van Gogh himself called it proudly, in a letter to his brother, ‘one of the ugliest pictures I have done.'

Van Gogh’s fees were different in different periods of his life and work, ranging from little to next to nothing. In 1882, he boasted (in a letter to his brother Theo) that he had succeeded in selling a painting of his — ‘… the first sheep has crossed the bridge.' But more often than not, he had to make do with bartering. At the start of his career, he usually paid his models with what he had painted. He tried hard to talk them into sitting nude for him — no doubt, he hoped for something more in the end, as the models he looked for, mostly girls of the port, were of quite loose morals. However, even the whores of Antwerp turned him down. It is hard to tell for sure what repelled the models more — the painter’s disagreeable and erratic nature or his artistic manner. Van Gogh never flattered a model and normally rendered likeness but very roughly, and the tints prevailing in his palette were depressive grey and brown.

Anyway, the only reward he occasionally received in those years was someone’s consent to sit for him. Later, in Paris, he met Agostina Segatori who ran the Café du Tambourin. Agostina, who herself ranked it as a museum rather than a café, agreed to take Van Gogh’s paintings as the price of food. She even frequently sent him flowers — not to express her admiration, though, but because she wanted the pictures she got from him to be more brightly coloured.

One of Van Gogh’s most celebrated paintings, The Night Café created in Arles became, too, his rent payment. The artist, who was then lodging in a room on the first floor, was in debt to the landlord. Vincent offered him, who ‘had taken so much of his money,' to paint his place, and the café owner had but to agree.

The room, normally crowded, has become almost empty in a flash (it was typical when Vincent would adjust his easel). We can see the unfinished glasses of wine, the carom billiards table left by the players, the tramps in the corners who have nowhere to escape and who are trying to hide their faces… The owner is the only one who is standing up and posing — as intrepid as one who has nothing to lose.

It turned out to be first-rate publicity. The Night Café made history as a visual meme symbolising loneliness, desolation, despair. Van Gogh himself called it proudly, in a letter to his brother, ‘one of the ugliest pictures I have done.'

Friends Of Bahasa

1910, 113×117 cm

Niko Pirosmani

A bottle of wine and some plain food — that was a typical fee of Nikoloz Pirosmanashvili, a homeless, starry-eyed altruist, a constant wanderer, a genius never recognised in his own lifetime. Most of his adult life he spent in taverns of Tiflis (now Tbilisi) colouring walls, painting sign-boards, making drawings on napkins and oilcloths. His life, as plain as his art, made some people admire him, others haughtily despised him, and others envied him secretly. Even those who knew him personally could not agree about who he was — a man of wisdom or a loony.

For some time, Pirosmani tried to blend in. He even started a dairy farm, but soon went bankrupt. Perhaps, the summit of his career as a businessman was his meeting the tavern-keeper Bego Yaksiev, who employed him as ‘a full-time painter.' At Bego’s, Pirosmanashvili had a full benefits package: a place to live, a closet he could use as his studio, good grub every day, and steam-bathing every Friday. Yaksiev loved Niko as if he had been his kinsman, and gave free rein to his artistic work. It was up to the painter to choose whether the sign-board would read Do not leave before wetting your whistle, or Wine, snaks, and a dyfferant waum food.

For several years Pirosmani lived at Bego’s, but finally, it was too much for the artist and he did a runner — and thus, among other things, pioneered downshifting.

A bottle of wine and some plain food — that was a typical fee of Nikoloz Pirosmanashvili, a homeless, starry-eyed altruist, a constant wanderer, a genius never recognised in his own lifetime. Most of his adult life he spent in taverns of Tiflis (now Tbilisi) colouring walls, painting sign-boards, making drawings on napkins and oilcloths. His life, as plain as his art, made some people admire him, others haughtily despised him, and others envied him secretly. Even those who knew him personally could not agree about who he was — a man of wisdom or a loony.

For some time, Pirosmani tried to blend in. He even started a dairy farm, but soon went bankrupt. Perhaps, the summit of his career as a businessman was his meeting the tavern-keeper Bego Yaksiev, who employed him as ‘a full-time painter.' At Bego’s, Pirosmanashvili had a full benefits package: a place to live, a closet he could use as his studio, good grub every day, and steam-bathing every Friday. Yaksiev loved Niko as if he had been his kinsman, and gave free rein to his artistic work. It was up to the painter to choose whether the sign-board would read Do not leave before wetting your whistle, or Wine, snaks, and a dyfferant waum food.

For several years Pirosmani lived at Bego’s, but finally, it was too much for the artist and he did a runner — and thus, among other things, pioneered downshifting.

A Chateau Mouton-Rothschild label with Pablo Picasso’s drawing

Pablo Picasso

Picasso was Pirosmani’s admirer, and once even painted a portrait of him. Besides, they had another thing in common: Picasso, too, had an experience of working for a tipple. Having been offered ten cases of wine, he drew a label for the celebrated Chateau Mouton-Rothschild. The company was forward-thinking enough to hold the work back and only released a line with Picasso’s label in 1973 — the year when the artist died. It was the year the winery ‘Mouton-Rothschild' triumphed. The label designed by the most famous artist of the 20th century was timed to appear on the market when the wine was awarded with the premium quality category in Bordeaux Wine Official Classification. How did ‘Mouton-Rothschild' succeed in hiring so expensive and uncompromising a designer for ten cases of wine only? The answer is quite simple: the ten cases of Chateau Mouton-Rothschild cost, at the very least, $ 100,000.

The tradition of inviting famous artists has been the company’s feature since 1945. Besides Picasso, they co-operated with Salvador Dalí, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Marc Chagall, Andy Warhol, Wassily Kandinsky, Ilya Kabakov and many more.

Picasso was Pirosmani’s admirer, and once even painted a portrait of him. Besides, they had another thing in common: Picasso, too, had an experience of working for a tipple. Having been offered ten cases of wine, he drew a label for the celebrated Chateau Mouton-Rothschild. The company was forward-thinking enough to hold the work back and only released a line with Picasso’s label in 1973 — the year when the artist died. It was the year the winery ‘Mouton-Rothschild' triumphed. The label designed by the most famous artist of the 20th century was timed to appear on the market when the wine was awarded with the premium quality category in Bordeaux Wine Official Classification. How did ‘Mouton-Rothschild' succeed in hiring so expensive and uncompromising a designer for ten cases of wine only? The answer is quite simple: the ten cases of Chateau Mouton-Rothschild cost, at the very least, $ 100,000.

The tradition of inviting famous artists has been the company’s feature since 1945. Besides Picasso, they co-operated with Salvador Dalí, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Marc Chagall, Andy Warhol, Wassily Kandinsky, Ilya Kabakov and many more.

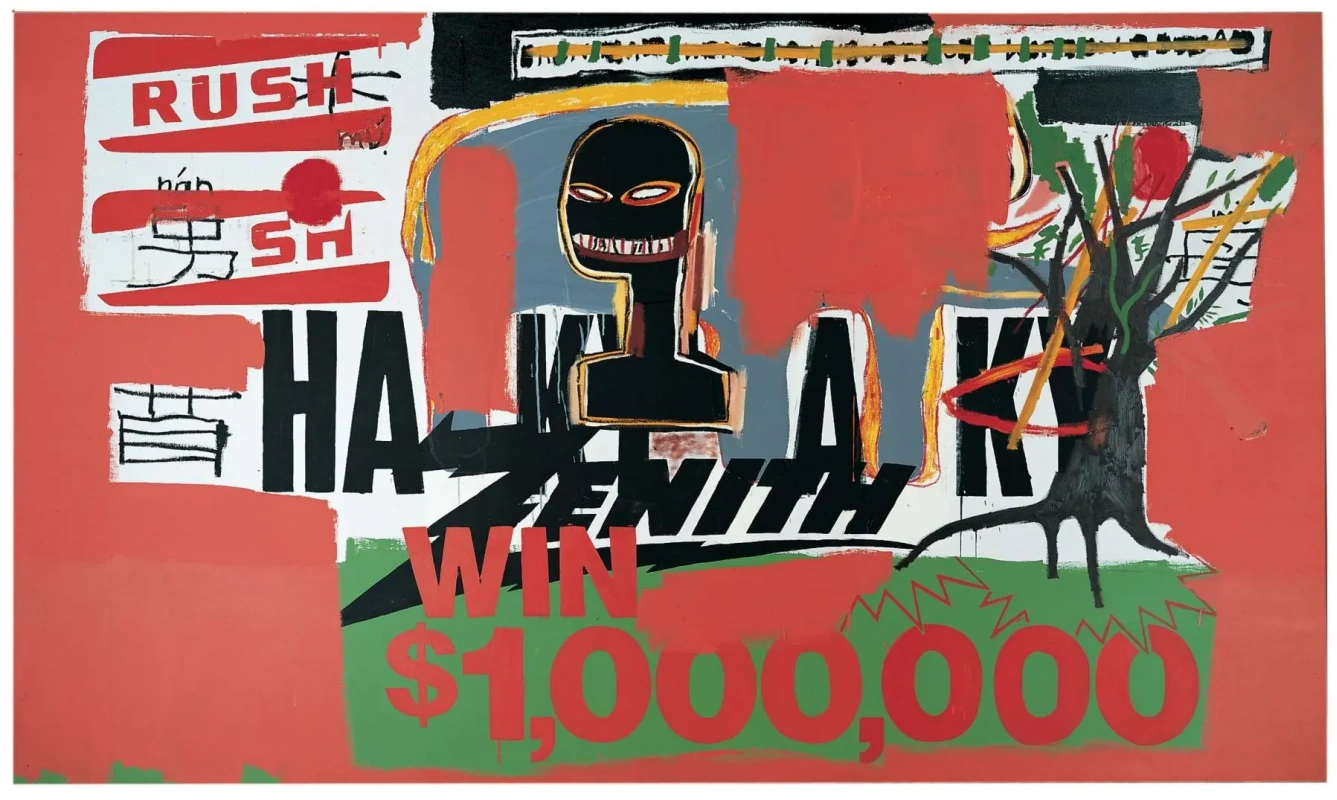

Text by: Andrei Zimoglyadov. Title illustration: Jean-Michel Basquiat. Win $ 1,000,000

We recommend reading

1 minParrot, «Embrace imperfection, because perfection is an elusive goal»: Interview with Irfan Ajvazi , 20241 minArtist Fred Bugs Biography1 minThe Paintings of John Wick Chapter 4: Decoding the Symbolism Behind the Paintings3 minA Closer Look at the Stunning Paintings in Coca-Cola's Latest Ad “Masterpiece”