Talking about the personal life of the most famous artist in the world is like walking on thin ice. He left no documentary evidence of his love affairs; no one really heard anything about his relations with women. There were persistent rumours about Leonardo da Vinci's relationships with men during his lifetime, and later they only grew stronger. For more than a quarter of a century, the artist took care of his student, known under the nickname Salai, but what were their relationship like in reality — no one would assert with absolute certainty. We only could try to imagine their story, based on the surviving information, including that of Leonardo’s authorship.

Unbearable boy

In his manuscripts, da Vinci sometimes resorted to an intricate method of writing with a mirror — the notes made in this way could not be read without the same device. He did this in cases when it was about things especially important to him.And one of these records read: "Giacomo came to live with me on the day of St. Mary Magdalene, 22 July 1490".

Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno was the full name of da Vinci’s new student. He was a ten-year-old boy at the time of his admission to the artist’s studio. He originated from Oreno, a small settlement near Milan. Nothing is known about his parents, except that in the documents, his father was called "the son of the last master Giovanni". This means that Giacomo’s grandfather had a certain status and could be a landowner.

At that time in Italy, sending such young boys as apprentices to artists and representatives of other craft professions, to which painters belonged during the Renaissance

, was a fairly common custom. They did all the work they could in the house and studio, and received their food and shelter as payment. If such an errand boy showed the ability to draw, later he received lessons in craftsmanship from his teacher and could become a painter himself. For example, it was the case with Pietro Perugino, who as a young man entered the studio of one of the artists in Perugia.

It was understood that the new inhabitant of da Vinci’s studio would also obey his master in everything and carry out all orders. But it turned out that from the very beginning he took a special position in the studio, testing the painter’s patience with his pranks. Leonardo’s patience seemed truly endless: despite the fact that Leonardo’s manuscripts are full of Giacomo’s daring antics, the boy not only kept living with him, but also enjoyed the privileges of luxurious clothes that da Vinci ordered for him.

It was understood that the new inhabitant of da Vinci’s studio would also obey his master in everything and carry out all orders. But it turned out that from the very beginning he took a special position in the studio, testing the painter’s patience with his pranks. Leonardo’s patience seemed truly endless: despite the fact that Leonardo’s manuscripts are full of Giacomo’s daring antics, the boy not only kept living with him, but also enjoyed the privileges of luxurious clothes that da Vinci ordered for him.

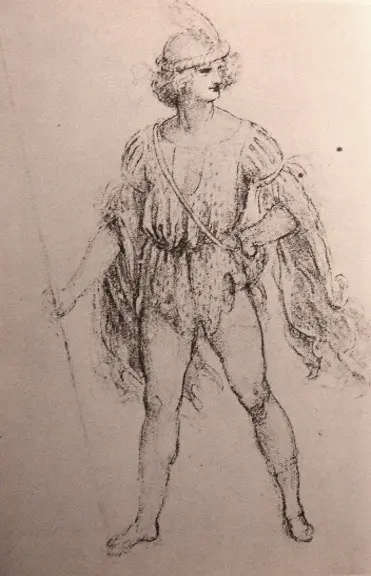

Profile Salai

1500

Less than a day later, he demonstrated his main talents: stealing and lying. "On the second day, I ordered two shirts, a pair of pants and a jacket to be tailored for him," complained Leonardo in a letter to the boy’s father. "And when I put the money aside to pay for these things, he stole the money from my wallet, and I couldn’t get him to confess, although I was firmly convinced of it." This did not prevent the artist from inviting the guilty servant the next day to accompany him at a dinner with his architect friend. The miracle did not happen: the little rantipole did things there: "And this Giacomo had supper as two and caused trouble as four, as he broke three decanters, poured wine," da Vinci wrote in the same letter and added a remark on margins: "Thief, liar, stubborn, glutton."

Little Devil

Convinced of his impunity, Giacomo commited more and more daring offenses. After a while, another student lost several silver coins and a silver drawing pin in Leonardo’s studio. During the search, the loss was found in Giacomo’s chest. And six months later, Leonardo received an order to make sketches of costumes for a festive tournament to coincide with the wedding of Ludovico Sforza. The boy was with him during the fitting and took advantage of the moment when the participants took off their clothes. "Giacomo got to the wallet of one of them, which was lying on the bed with all the other clothes, and pulled out the money he found in it," wrote Leonardo. "Just a similar case, when Master Agostino di Pavia gave me Turkish leather for a pair of shoes in the same house, this Giacomo stole it from me a month later and sold it to a shoemaker for 20 soldi, for which, as he himself confessed to me, he bought anise sweets".

The Penitent Magdalene

1520, 65×51 cm

It is no wonder that for his tricks the young man eventually received the appropriate nickname, Salai, diminutive — Salaino. In Tuscan dialect, it means demon or imp and is first mentioned in a payment document authored by da Vinci, dated January 1494.

Perhaps he borrowed this name from the character of the Morgante knightly poem by the Italian Luigi Pulci, a book that was kept in the artist’s library.

What held da Vinci back from getting rid of the dodgy rascal once and for all? Perhaps the answer is in the testimony of Vasari, who noted that Salai was "very attractive for his charm and beauty, had beautiful curly hair that curled in rings and was very liked by Leonardo". The artist generally paid a lot of attention to the aesthetics of appearance. He regularly visited the barber, took care of his hairstyle and even dyed his hair when grey began to appear. The Florentine author Anonimo Gaddiano described the artist’s appearance as follows: "A pleasant gentleman, well-built, graceful, attractive in appearance. He wore a pink cape that reached to his knees, whereas they wore long robes in that era. He had a beautiful, curly, well-styled hair that fell to the middle of his chest."

Perhaps he borrowed this name from the character of the Morgante knightly poem by the Italian Luigi Pulci, a book that was kept in the artist’s library.

What held da Vinci back from getting rid of the dodgy rascal once and for all? Perhaps the answer is in the testimony of Vasari, who noted that Salai was "very attractive for his charm and beauty, had beautiful curly hair that curled in rings and was very liked by Leonardo". The artist generally paid a lot of attention to the aesthetics of appearance. He regularly visited the barber, took care of his hairstyle and even dyed his hair when grey began to appear. The Florentine author Anonimo Gaddiano described the artist’s appearance as follows: "A pleasant gentleman, well-built, graceful, attractive in appearance. He wore a pink cape that reached to his knees, whereas they wore long robes in that era. He had a beautiful, curly, well-styled hair that fell to the middle of his chest."

The heads of old and young men

1495, 20.8×15 cm

Presumably, in this drawing, da Vinci portrayed himself as a decrepit old man next to Salai full of youth.

Da Vinci never spared money to dress up his student like a favourite toy. One of the artist’s notes describes the necessary materials to sew a luxurious cloak of silver brocade with green velvet trim for the young man. Leonardo’s expenses on clothes for Salai in the first year of his stay in the studio were approximately the amount that a servant received on average per year. This money was used to buy twenty-four pairs of shoes, four trousers, six shirts, three jackets, a linen camisole, a coat and a hat. Later manuscripts indicate that da Vinci forked out for a chain for his favourite, a sword and even a trip to a fortune-teller. And another time he gave Salai three gold ducats just because he asked to buy him pink patterned stockings. A week later, he allowed him 21 cubits of linen for a shirt worth more than ten lire, which amounted to a six-month salary of servants at that time. The maintenance of a simple apprentice cost the artist much.

A riddle, wrapped in a mystery

As we already mentioned, reliable information about the personal life of Leonardo da Vinci has not been preserved. He himself never wrote about his love affairs, despite the habit of rather meticulously reporting even the smallest details of his daily routine in his manuscripts. Perhaps this was due to the fact that his heartfelt affection could lead to serious accusations at the time. And in the life of the artist there was already a similar precedent.

Lady with an ermine. Cecilia Gallerani

1480-th

, 54.8×40.3 cm

The heroine of this portrait, according to most researchers, was the mistress of Ludovico Sforza, the only woman suspected of having a relationship with da Vinci: because of a draft of a letter supposedly addressed to her. It began with the address: "My beloved goddess…". But due to the lack of other evidence, this version is considered unlikely.

In the 15th century, sexual relationship between men in Florence became so widespread that the slang term for homosexuals was even introduced in German, "Florenzer", which means a Florentine. Over time, the rulers of the city began to take measures to suppress this "fashion", creating special committees and imposing severe punishments, including burning at the stake. Fortunately, it rarely came to this: the sentence was mostly limited to a fine, but for repeated violation people could be imprisoned in stocks outside the prison building.

Disguised in the image of the prisoner

1517, 18.2×12.7 cm

In addition, boxes known as "holes of truth" were installed on the streets of Florence. Residents of the city could anonymously leave letters with a story about violators of various laws and regulations. And in 1476, in such a box, a letter was found accusing Leonardo da Vinci in relationship with the seventeen-year-old Jacopo Saltarelli. And although another similar accusation, in Latin, appeared a couple of months later, the artist was not convicted. Neither the authors of the denunciations, nor any witnesses appeared at the court session, and anonymous denunciations were not enough to pass the verdict.

However, everyone remembered this case, and it could become the reason that da Vinci was afraid to mention his personal life in his manuscripts. Although this did not prevent some researchers from confidently asserting about his homosexual orientation, and the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud was among them. In many ways, such interpretations were facilitated by some of the artist’s statements. He wrote: "The act of childbirth and everything that has anything to do with it is so disgusting that people would soon die out if there were no beautiful faces and sensual inclinations." And more: "Intellectual passion displaces sensuality… Whoever does not curb lustful desires, puts himself on the same level with beasts."

Although the last entry can be interpreted not only as an attempt to suppress the impulses condemned by the environment, but also as a complete refusal of da Vinci from any kind of sexual relations in principle. Therefore, some researchers of his biography preferred to conclude that the artist remained celibate throughout his life. If they are right, then his heartfelt affection for the young apprentice was exclusively platonic and based on the aesthetic pleasure of seeing a golden-haired imp with the appearance of an angel.

There is not a single documented portrait of Salai, but the characters in some of da Vinci’s paintings are suspected of being painted from his thieving student. And not only men: even La Gioconda was included in this list. Among the male characters, the similarity with him is attributed to John the Baptist, the apostles Philip and Matthew from the The Last Supper fresco.

Life without Salai

Da Vinci’s parting with his life partner after almost three decades was as mysterious as their relationship. The artist did not say a single word in his notes what happened between them, after which Salai left his house forever. Only one thing is known: when in 1519 Leonardo got concerned with making a will, Giacomo was no longer with him. Although this did not stop da Vinci from mentioning him in this document, in contrast to the manuscripts, in which he would never write a single line about his golden-haired apprentice.

John The Baptist

XVI century, 73×51 cm

Salai is credited with a painting depicting St. John the Baptist — in the same pose as in Da Vinci’s painting, but even more effeminate and playful.

The artist spent his last years in the company of his new favourite, Francesco Melzi. He was the son of a Milanese aristocrat, whom da Vinci often visited in his estate near Milan. The boy was good-mannered, had a brilliant education and a penchant for drawing. He was captivated by the intellect and artistic talent of Leonardo, and his father sent 15-year-old Francesco to his idol’s studio as an apprentice. The young man admired the genius and remained loyal to him until his death. And da Vinci was fascinated by his youth: "Melzi's smile makes me forget about everything in the world," he wrote.

1Flora

1520, 76×63 cm

In a sense, the new student was the complete opposite of Salai. He had the gift of a diplomat and helped the artist maintain relationships with influential people, as they were sometimes threatened by da Vinci’s tempestuous disposition. Despite the 41-year age difference, they had a truly trusting relationship, as mentioned by Leonardo in his notes. He entrusted Francesco with the task of organizing his manuscripts: he had to classify, rewrite them cleanly and prepare them for printing. The result of this titanic work was the famous Atlantic Code, a manuscript consisting of 1,119 pages. Melzi surrounded the artist with touching care and was his loyal companion for 11 years until da Vinci’s last breath.

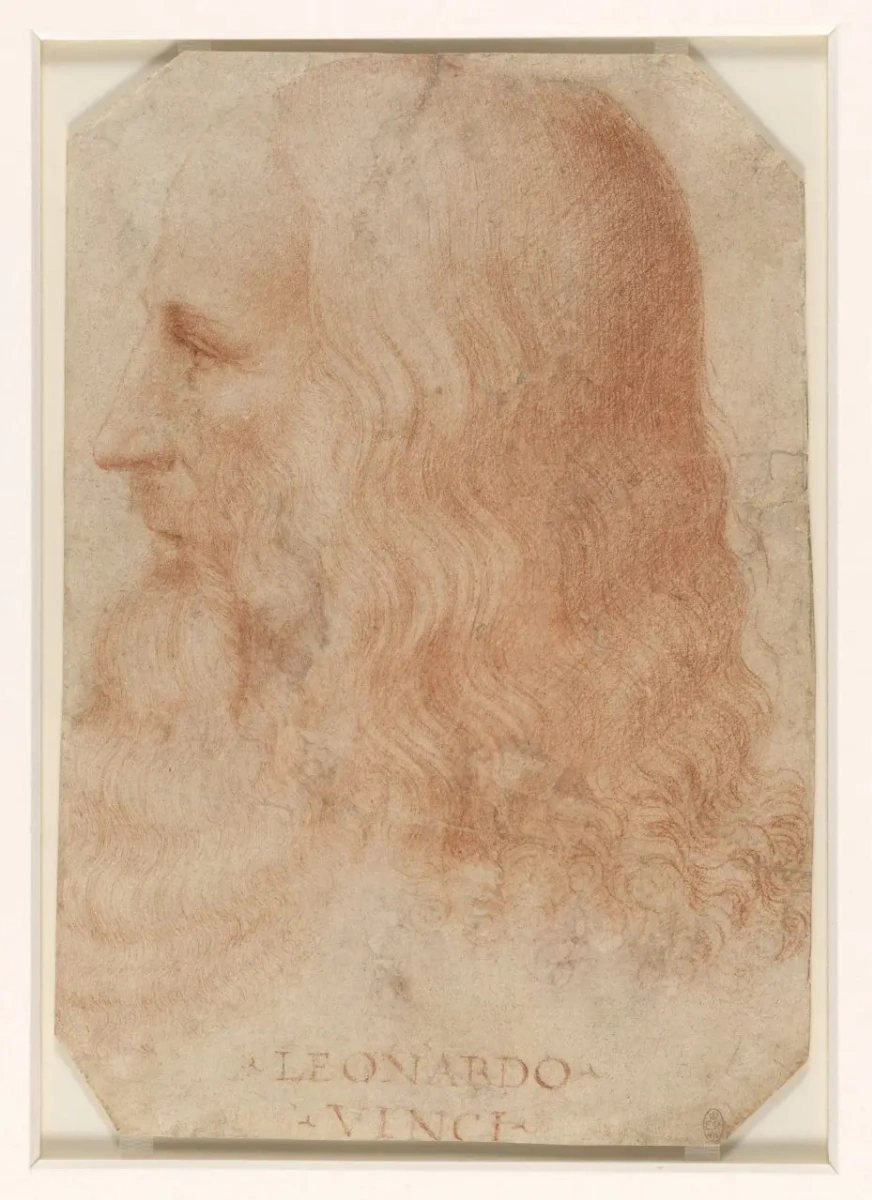

A portrait of Leonardo

1517, 27.5×19 cm

According to his will, Leonardo divided the most valuable things he had, "his own garden located outside the walls of Milan", between Salai and another servant, Battista de Villanis. In August 1497, he received a piece of land with a small house and a vineyard from his patron Ludovico Sforza, presumably as a fee for painting The Last Supper. Owning his own land was an important indicator of status at the time, especially that the site was located next to the estates of the Milanese nobility. Salai built a house on his site, and on 14 June 1523, he brought his new wife Bianca Caldiroli there. An important factor in the matter of Salai’s marriage could be an impressive dowry of 1,700 lire. But he did not enjoy his newfound home, family, and sudden wealth for long.

On 15 January 1534, Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno died at the age of 44 wounded by a gunshot.

On 15 January 1534, Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno died at the age of 44 wounded by a gunshot.

Artists mentioned in the article

We recommend reading

11 minRock-solid Leonardo. Why the Louvre Considers the Saviour of the World a Creation of the Genius23 minIcon painting21 minFrescoes and Ash. Painting and Design in Ancient Pompeii1 minPuzzle Parking System

1 minParrot, «Embrace imperfection, because perfection is an elusive goal»: Interview with Irfan Ajvazi , 20241 minArtist Fred Bugs Biography1 minThe Paintings of John Wick Chapter 4: Decoding the Symbolism Behind the Paintings3 minA Closer Look at the Stunning Paintings in Coca-Cola's Latest Ad “Masterpiece”