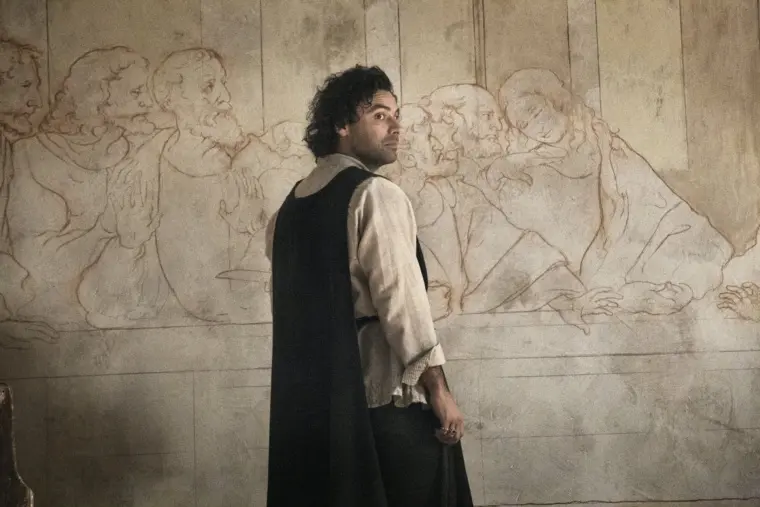

The Leonardo series was released in March. Aidan Turner, the handsome dwarf Keely from Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit trilogy, starred in the eight-part story based on the life of da Vinci. The script author were Frank Spotnitz (his portfolio includes The X-Files and Medici series) and Steve Thompson (author of Sherlock and Doctor Who). It turned out to be a detective story with a touch of melodrama. The plot is based on something that never happened: Leonardo is accused of the murder of his girlfriend and awaits his death sentence in a prison cell.

Fiction prevails over facts here; the latter are assigned, rather, the role of seasoning. This series can raise a number of questions from those who have already watched it, and those who are just going to do so, and even those who are not going to waste time watching. Arthive answers the main questions.

Have they made it?

The one whom we consider the number one artist was also loved by his contemporaries for his ability to organize the most incendiary parties, create the most spectacular performances and carnivals (he once designed a lion that came to life, opened its chest and released blue balls with golden lilies inside), conduct fascinating conversations and entertain the sophisticated court audience (including riddles he composed himself).

If Leonardo da Vinci lived today, he would compete with Elon Musk on the basis of invention, direct large-scale shows like the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games, be a hero of gossip columns and covers of glossy magazines. Maybe he would even produce TV series: after all, at present day, they are the best means for realizing great creative ambitions. Therefore, you would likely expect a corresponding experience from the series about Leonardo, hope that the creators would at least try to surprise you in the same way as did Leonardo to the audience more than 500 years ago.

Indeed, in the process of preparation, they learned so much about Leonardo’s ambitions: it should be contagious, it should make them at least aim at an outstanding, unprecedented work.

They didn’t even give it a try.

In interviews, they said that they wanted to explain what the genius of Leonardo was. But in fact, they just used the usual set of clichés for films about artists. Leonardo is lonely and unhappy: talking about his childhood, the artist weeps and says that he lived literally in the mud, although there is every reason to believe that the notary father and grandfather, in whose house Leonardo grew up, took good care of him.

Leonardo is unsociable, and his speeches are incomprehensible to those around him: this is not surprising, because at a time when all the other characters in the series speak like real people (whereas Leonardo’s girlfriend Caterina resembles a broken heroine of 1990s romantic comedies with her behaviour and speaking manner), da Vinci utters phrases copied from the surviving diary entries.

The heroes of the series do not express their feelings, do not hint at the motives of their actions, they just speak everything out. In all fairness, the drama so low is disheartening in a 2021 series. This script looks as if written by people who have nothing to say about Leonardo.

If Leonardo da Vinci lived today, he would compete with Elon Musk on the basis of invention, direct large-scale shows like the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games, be a hero of gossip columns and covers of glossy magazines. Maybe he would even produce TV series: after all, at present day, they are the best means for realizing great creative ambitions. Therefore, you would likely expect a corresponding experience from the series about Leonardo, hope that the creators would at least try to surprise you in the same way as did Leonardo to the audience more than 500 years ago.

Indeed, in the process of preparation, they learned so much about Leonardo’s ambitions: it should be contagious, it should make them at least aim at an outstanding, unprecedented work.

They didn’t even give it a try.

In interviews, they said that they wanted to explain what the genius of Leonardo was. But in fact, they just used the usual set of clichés for films about artists. Leonardo is lonely and unhappy: talking about his childhood, the artist weeps and says that he lived literally in the mud, although there is every reason to believe that the notary father and grandfather, in whose house Leonardo grew up, took good care of him.

Leonardo is unsociable, and his speeches are incomprehensible to those around him: this is not surprising, because at a time when all the other characters in the series speak like real people (whereas Leonardo’s girlfriend Caterina resembles a broken heroine of 1990s romantic comedies with her behaviour and speaking manner), da Vinci utters phrases copied from the surviving diary entries.

The heroes of the series do not express their feelings, do not hint at the motives of their actions, they just speak everything out. In all fairness, the drama so low is disheartening in a 2021 series. This script looks as if written by people who have nothing to say about Leonardo.

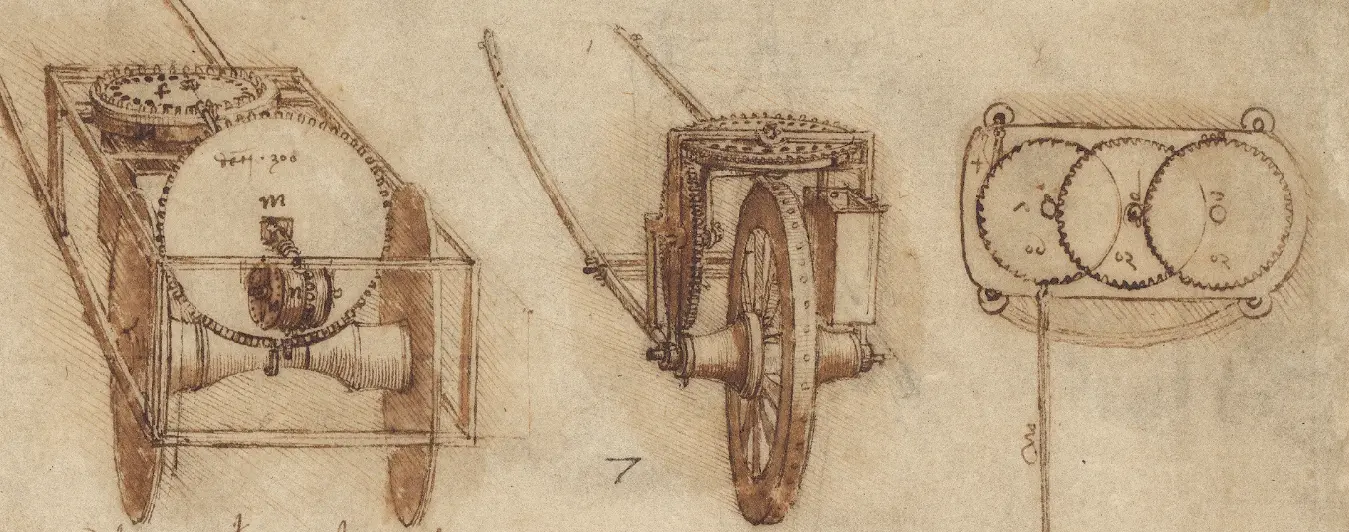

There are moments in the series that will delight the connoisseur of da Vinci’s creativity and biography. For example, we are shown what the portrait of Ginevra de Benci looked like before its lower part was cut off, and they explain what the plants in this portrait are hinting at. We see a working odometer invented by Leonardo — a funny wheelbarrow for calculating distances on the ground. But the giant crossbow appears only as a picture on the screen. This exactly corresponds to reality: like many other inventions of Leonardo, it was only realized on paper. But this is a series in which the authors do not hold back their fantasy, so why not revive Leonardo’s fantasy in it? However, the revived giant crossbow of da Vinci can be seen in another series, in the eighth season of Game of Thrones.

About the facts. Their presence in the series creates some problem. They tell you how Leonardo painted a fresco on dry plaster, how he studied the anatomy of a horse to design an equestrian statue, how he made The Battle of Anghiari cartoons and how he abandoned this venture. All this was in fact and can give the impression that Leonardo was also hanged in Piazza, as well as he knew how to revive people: wow, I didn’t know that! Neither facts nor fantasies in the series are marked in any way, whereas the viewer is not obliged to watch it armed with biographical books. It seems that the authors had to decide: either to stick to the facts, or to come off in full, so that the whole story looks invented, unreal.

About the facts. Their presence in the series creates some problem. They tell you how Leonardo painted a fresco on dry plaster, how he studied the anatomy of a horse to design an equestrian statue, how he made The Battle of Anghiari cartoons and how he abandoned this venture. All this was in fact and can give the impression that Leonardo was also hanged in Piazza, as well as he knew how to revive people: wow, I didn’t know that! Neither facts nor fantasies in the series are marked in any way, whereas the viewer is not obliged to watch it armed with biographical books. It seems that the authors had to decide: either to stick to the facts, or to come off in full, so that the whole story looks invented, unreal.

Did they make Leonardo a gay?

To be fair, many viewers liked the Leonardo series: there are already a lot of enthusiastic reviews on Internet, including comments to Arthive’s posts on social media. This is a well-known phenomenon: the public is often condescending to films about artists, transferring their love for art and individual creators to mediocre works telling about them. Spectator outrage is also there, but its subject is not helpless drama or sloppy dialogues at all. A common claim sounds like this (a literal quote from a forum follows): "I don’t believe that Leonardo was bicurious, it’s European values that dictated the script for the movie."

In fact, everything is exactly the opposite. The film scriptwriters dealt as delicately as possible with Leonardo’s homosexuality, which was the subject of jokes and gossip for the artist’s contemporaries. Over the course of eight episodes, Leonardo kisses three men, but never takes the initiative: he looks more like an asexual who only responds to the actions of others. And the story of Leonardo’s relationship with his student Salai in the series is brought in line with our today’s ideas about morality, so as not to shock the viewer. In the series, Giacomo, who has yet to get the nickname Salai (the imp) for his antics, comes across da Vinci as a young man, apparently an adult. And the facts are as follows: when 38-year-old Leonardo made the entry "Giacomo settled with me" in his diaries, the boy was only 10 years old. Moreover, on the screen, Leonardo looks rather brutal, while in fact he was interested in ways of dyeing and curling his hair no less than the study

of chiaroscuro and anatomy, and the artist’s contemporaries were fond not only of his paintings, but also short pink cloaks above his knees he wore.

And yet, the creators of the series were also guided by modern trends. Today it is considered mauvais ton to release works without strong female characters. Leonardo met extraordinary women on his path, the authors had much room to create. But Ginevra de Benci was given only a small episode, Cecilia Gallerani is not among the characters at all (her portrait with an ermine only appears in the frame

for a split second), instead they invented a platonic love named Caterina da Cremona for Leonardo.

Caterina da Cremona: who was the first to come up with a close friend for Leonardo?

This is fiction, but its roots go back to the early 19th century.Italian artist and writer Giuseppe Bossi (1777—1815), who devoted his whole life to studying da Vinci’s work (he copied The Last Supper, drew episodes from the life of Leonardo, made articles about him), in his essay on the embodiment of passions in art, expressed the following thought: "The fact that Leonardo… loved the joys of life is proved by the records of his relationship with a courtesan named Cremona. I received these records from a very authoritative source. He could not have understood human nature so deeply and embodied it without long experiencing it through purely human weaknesses."

Bossi did not reveal his source. But in 1982, Bossi’s works were reprinted and got to the British writer Charles Nicholl, who developed this idea in his 2004 book Leonardo da Vinci. The Mysteries of a Genius. And he even drew some evidence in its favour. For example, in the Windsor collection, he found a sheet from Leonardo’s notes, in the lower right corner of which there was a list of six names, one of them being Chermonese. Nicholl came to the conclusion that the list included people who accompanied Leonardo on a trip in 1509, and Chermonese was a courtesan from Cremona, with whom the artist allegedly had a relationship.

Nicholl believes that Bossi meant a prostitute by the courtesan, therefore he found two representatives of this profession named Maria Cremonese in the Roman census of 1511—1518 and made the assumption that da Vinci met his La Cremona in Rome. In addition, Nicholl stated in his book that the courtesans "lived in the houses of candle-makers and lantern-sellers".

He also suggested that Leda’s face in Leonardo’s lost painting is that of La Cremona.

Nicholl concluded his assumptions with the following passage: "It is not difficult for me to imagine that fifty-seven-year-old Leonardo had some kind of relationship with a beautiful young prostitute, whose serene face and magnificent body served as a model for his Leda, and perhaps for the lost Nude Gioconda. The assumption opens up a new page for us in the artist’s sexual life and refutes the theory that he was absolutely homosexual… Whatever the artist’s preferences, it is unlikely that this ‘student of experience', who sought to know everything possible, would deny himself in the sexual knowledge of women. The Cremona mentioned by Bossi could teach him heterosexual ‘joys', lack of which would make the understanding of life incomplete."

He also suggested that Leda’s face in Leonardo’s lost painting is that of La Cremona.

Nicholl concluded his assumptions with the following passage: "It is not difficult for me to imagine that fifty-seven-year-old Leonardo had some kind of relationship with a beautiful young prostitute, whose serene face and magnificent body served as a model for his Leda, and perhaps for the lost Nude Gioconda. The assumption opens up a new page for us in the artist’s sexual life and refutes the theory that he was absolutely homosexual… Whatever the artist’s preferences, it is unlikely that this ‘student of experience', who sought to know everything possible, would deny himself in the sexual knowledge of women. The Cremona mentioned by Bossi could teach him heterosexual ‘joys', lack of which would make the understanding of life incomplete."

The authors of the series enhance this fantasy. Their Cremona is not Maria, but Caterina. She’s not exactly a courtesan (at least when she meets Leonardo), but she sells candles and easily gets along with guys. At the time of the beginning of their friendship, Leonardo is not 57 years old and this does not happen in Rome: he is still very young, lives in Florence, studies under Verrocchio. But he would still paint his Leda from her in the series. And most importantly, the discrepancies in the two versions of the legend: in the series, there are no bodily joys between Leonardo and Caterina.

The Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones uses strong words in his review of the series: "Caterina is fiction, fantasy, complete nonsense, invented by a 19th century romantic and given the rather unconvincing trust of one modern biographer, Charles Nicholl, for some reason."

But is there anything good in this series?!

Yes! There is one very charming character in the series; unfortunately, he only appears in a couple of scenes. This is the young Michelangelo who, in reality, could claim to be the most unpleasant artist in the history of art. Here he is charming. Especially at the beginning of his competition with Leonardo (they tried to paint frescoes on the opposite walls of a hall) when he showed him his butt.- A still from the series. Michelangelo got down to work, but hides it behind a curtain. Leonardo is assailed with creative jealousy and curiosity. Michelangelo removes the veil and joyfully shows his opponent the following.

- Battle of Cascina. Copy from a cartoon of Michelangelo’s unmade fresco. Ca. 1542. Holkham Hall, Norfolk

Is there a scene in which da Vinci paints The Saviour of the World with his own hand?

Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World)

1500, 65.7×45.7 cm

There is no such scene. Perhaps, if the mysterious owner of this picture, the most expensive picture in the world, had agreed with the series authors about the plot course to support the version that Leonardo was the author of the Saviour, then the series would have had a more impressive budget, which could provoke and inspire screenwriters. But they did not work it out.

Artists mentioned in the article

We recommend reading

27 minAndrei Tarkovsky. The captured masterpiece paintings4 minThe Basquiat movie: an atmospheric fairy tale with great actors14 minLone Warrior: 10 Most Expensive Paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat1 minParrot, «Embrace imperfection, because perfection is an elusive goal»: Interview with Irfan Ajvazi , 2024