Why would the proletariat need high art? The country needs technology! "The paintings in the Hermitage will not be any worse", the leaders thought when they invited millionaire buyers from abroad. The madness of the dark time: when people disappeared without a trace, who would regret the paintings? Botticelli, Rembrandt, van Eyck, Raphael, Titian, Rubens — the young Soviet government exchanged hundreds of painting masterpieces for tractors.

At night, a prison van drove up to the entrance of the Hermitage, exactly the same as those that carried people away. Those who saw it were seized with the usual feeling of numbness and horror. But this time the black car came not for people, but for… paintings. In the morning, instead of the disappeared canvases, there appeared signs "The painting taken for photographing" or "The painting is being restored". Sometimes, if too many pictures were missing, the rest of them were rearranged so that no voids were noticeable. No one saw these masterpieces again — the priceless cultural treasures disappeared from the Soviet Union forever.

The Hermitage

In the beginning, there was the idea of a "proletarian" Hermitage. Valuable and experienced museum workers, who dedicated decades of their lives to the museum, were expelled only for their belonging to a noble family. They were called "trash" and "socially inferior elements" and thrown out of the main museum of the country. As a result, there was no one left who could resist the incipient absurdity.

Today, the Hermitage staff throw up their hands in bewilderment and call those events madness, "a tragedy, a catastrophe, a senseless and deplorable activity in terms of its results".

The adoration of the Magi

1482, 68×102 cm

But in those days, in a whirlwind of revolutionary cataclysms, against the background of crumbling churches, which perished in the fire of icons and other intoxicating blasphemy, everything seemed natural and logical. Building a bright communist future required financial injections and economic support. The economy of the Soviet country was in a deplorable state. The hungry country needed bread, Western tractors, excavators and other equipment. And "gazing" at pictures in museums doesn’t make you full! This is how the "brilliant" idea arose to sell the alien art of the past centuries to the no less alien West.

The Hermitage hall

The Hermitage: shall we start?

The first one who came up with the "brilliant" idea of selling painting masterpieces from museum abroad was the very leader of the proletariat, Vladimir Lenin. By 1918, thanks to the efforts of Russian collectors, as well as the imperial family, Russia possessed numerous collections of painting masterpieces. In addition to Catherine II, who began to collect the Hermitage collection, Nicholas I, Alexander I and other members of the imperial family also collected paintings for the museum, spending huge amounts of money for this. So the Hermitage and other museums in the country had something to please the West! Back in the 1920s, Lenin wrote that objects of art must be sold legally, and that this must be done "extremely quickly". This extremely "practical" idea was later boosted by Comrade Stalin.

The only person in the government who understood the blasphemy of what was happening was People’s Commissar A. V. Lunacharsky, but no one heard him.

For this purpose, a special Antiques office was organized. Through this organization, the most famous masterpieces of painting, from Rembrandt to Rubens, were sent abroad very quickly. There was no one in the Hermitage to resist such "cheerful" entrepreneurship. Thus began one of the most shameful pages in the history of the USSR — the Stalin’s sale of paintings of 1929—1934.

The first tipster

The main informant of the West, who provided reliable information about the treasures in Soviet Russia, was the Englishman Martin Conway, who arrived in the USSR in 1924 and was greeted very warmly. In his book, he noted how the "amiable" Russians took him to the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, famous palaces, and, of course, to the Hermitage, where they left him "all alone" for the whole day, to take a closer look. An enterprising Englishman made the necessary advertising for the cultural heritage of the Soviet republic, and the first swallows (or rather, vultures) soon reached the USSR: buyers, like moths attracted by the alluring fire of an incredible offer of the museum treasures sale.

It’s all about the oil!

The first "purchaser" of the Hermitage paintings was Calouste Gulbenkian, an Iraqi oil magnate. The Portrait of Titus by Rembrandt, Bathers by Lancret moved into his collection. But even he, despite the obvious benefit for himself, as a cultured person, realized the absurdity of what was happening. After all, no country knew such precedents! "Trade whatever you want, but not what is on display in the museum. The sale of a national treasure gives basis to a very serious diagnosis," he wrote in a letter to G. L. Pyatakov. "Such deals cause enormous damage to the prestige of the country and its culture" — alas, the irreparable events continued.

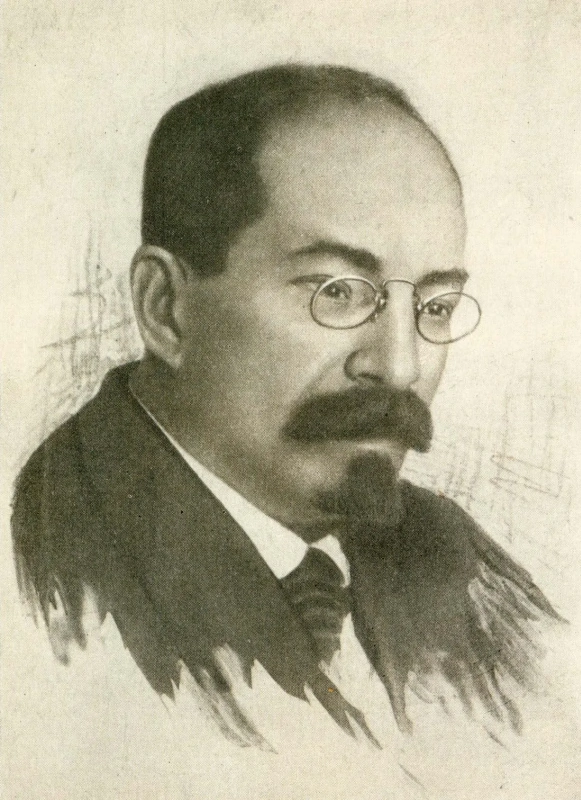

Iraqi oil magnate Calouste Gulbenkian, the first buyer of the Hermitage paintings.

Certainly, some cultural figures tried to resist. But the head of Vneshtorg, Anastas Mikoyan, only laughed, because he was a forced man, and the decrees came from "above". And if we take into account the hopes for a world revolution, then the sale of paintings can be considered a "loan", and someday they will definitely come back! There were no objections to such a frivolous turn from the defenders for the national culture, they were stunned and left with nothing. Maybe this was the arbitrariness of officials? There were letters written even to the leader himself, Comrade Stalin, and he even considered them, however this did not give any tangible results, since he himself had decreed the sales course.

Venus with a mirror

1555, 124.5×105.5 cm

“Client” No. 2

The second most famous buyer of the museum paintings was the American financial "king" and minister Andrew Mellon. Later, in his memoirs, he would recall the servility of Vneshtorg employees taking him to museums, assuring him that "they sell anything from any museum, and he is free to buy any painting or thing at his discretion". Here Mellon really bought painting masterpieces for a song. In April 1931, Mellon bought 21 priceless masterpieces for only $ 6,654,053. Already four years later, these paintings were appreciated eight times more expensive. And after the war, they cost just incredible money — one hundred million dollars. Mellon could have become a major millionaire simply by reselling the canvases bought in the Union.

St. George and the Dragon

1506, 28.5×21.5 cm

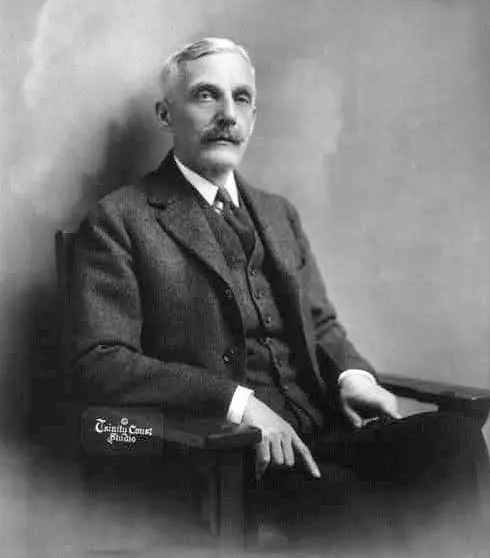

Andrew Mellon, the financial "king" of America

At the same time, it is curious that these barbaric sales of paintings were kept in deep secrecy. And the answers to direct questions from Soviet diplomats abroad were unequivocal: no, there are no paintings for sale! All right, "individual purchases" would be a different matter, but the auction was no longer possible to hide, and the sale of paintings turned into a Punchinel’s secret. At several sales in Berlin and Leipzig, 256 masterpieces of world painting were sold for a pittance. Among them were paintings by Rubens, Rembrandt, Falcone, Cranach the Elder.

The Hermitage paintings: sold epochs

Using the example of the Hermitage, let us summarize: what kind of pictures did the country get rid of during the Stalin’s sales. From the museum’s funds, 2880 paintings were put up for sale, of which 48 masterpieces left the country forever. These were canvases of Jan van Eyck, Rembrandt, Raphael, Titian. The collection of Flemish and Dutch paintings and other collections donated to the museum by the country’s most famous collectors in the past were partially sold out. For example, Van Eyck’s Annunciation and Raphael’s Madonna Alba were sold to Mellon. At the auctions, Head of an Old Man in a Cap by Rembrandt, Portrait of an Old Man by van Cleve, Saint Jerome and Madonna and Child by Titian, paintings by Cantarini, Berne, Canaletto, Moroni were sold. The Assumption of the Virgin Mary by Rubens, The Last Supper by Van Dyck, The Massacre of the Innocents by Giorgione and many more paintings — the former pride of the country and its cultural heritage — have forever disappeared from the Hermitage.

Assumption Of The Virgin Mary

1618, 423.3×281 cm

Who took over the baton?

Half of the paintings so easily given away by the Soviet Union are now in the national museums of America. So, in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, you can now admire the Birth of Venus by Nicolas Poussin. Initially, the painting was donated to the Hermitage by Catherine II, and the Museum does not hide the fact that it was bought in the USSR — you can even read about it in the comments under the painting. Three Hermitage paintings, The Crucifixion and The Last Judgment by Jan Van Eyck and The Lute Player by A. Watteau, took their place of honour in the New York Metropolitan. 51 (!) objects of art from the Hermitage, including paintings, migrated to the Gulbenkian collection. Then he sold them to museums and private collections, and most of the paintings can be seen in the Lisbon Museum of the Gulbenkian Foundation now.

Portrait of Pope innocent X

1650, 49.2×41.3 cm

The collection of Mellon, who bought 21 paintings in the USSR, is now in the US National Gallery of Art. Madonna Alba and St. George and the Dragon by Raphael, Adoration of the Magi by Botticelli, Study

after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X reside there now.

The Alba Madonna

1511, 94.5×94.5 cm

The list could be long. And, which is completely paradoxical and incredibly insulting, the income from the sale of these paintings was so scanty (no more than 1% of the country’s gross income) that it did not actually affect the development of the economy. But the damage to the international reputation and culture of the country was irreparable.

Arthive: follow us on Instagram

The article was prepared based on materials from various Internet publications.We recommend reading

1 minParrot, «Embrace imperfection, because perfection is an elusive goal»: Interview with Irfan Ajvazi , 20241 minArtist Fred Bugs Biography1 minThe Paintings of John Wick Chapter 4: Decoding the Symbolism Behind the Paintings3 minA Closer Look at the Stunning Paintings in Coca-Cola's Latest Ad “Masterpiece”