Orientalism is a whole complex of ideas, images and techniques that took shape in the works of West European artists of the 19—20th centuries under the influence of the legends about East and Eastern literature, personal travels and scientific works and, finally, under the direct influence of oriental fine art.

Orientalism is not an independent art style, but rather a certain image of the Orient, the opposite of the image of the Occident. This is the way and the process of cognition of the East, which was taken by not only Western artists and sculptors, but primarily sociologists, linguists, anthropologists, philosophers. And in this sense, orientalism is a universal term. The linguists who study

Semitic languages and the writers who put their heroes in some Algerian harem, and the composers who weave and stylize oriental melodies in symphonies and operas are also orientalists. Even some French collector who hungs Turkish arms and carpets in his bedroom and walks around the house in a turban could be an orientalist.

But we are interested, of course, in the oriental influences on Western art: Turkish baths in the paintings by Dominic Ingres, Gauguin’s searches for an earthly paradise in Oceania, the influence of Japanese engraving on the pictorial language of Vincent van Gogh and Edouard Vuillard, and the impact of the African masks on the form perception of Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti.

But we are interested, of course, in the oriental influences on Western art: Turkish baths in the paintings by Dominic Ingres, Gauguin’s searches for an earthly paradise in Oceania, the influence of Japanese engraving on the pictorial language of Vincent van Gogh and Edouard Vuillard, and the impact of the African masks on the form perception of Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti.

Where was the Orient?

For a West European artist, the famous and often imagined Orient was quite small: the Ottoman territories, which changed multiply during the 19th century, India and North Africa. Simply put, those were the countries which adjoined the Mediterranean, were European colonies or were available for trade.Already in the middle of the 19th century, after America had signed the trade agreement with Japan, the country, which had been closed until then, became a new object of study and a source of inspiration. Finally, by the end of the century, in search of an earthly paradise and following the routes of the colonialists, artists reached the farthest places, behind which there was only America. That was Polynesia.

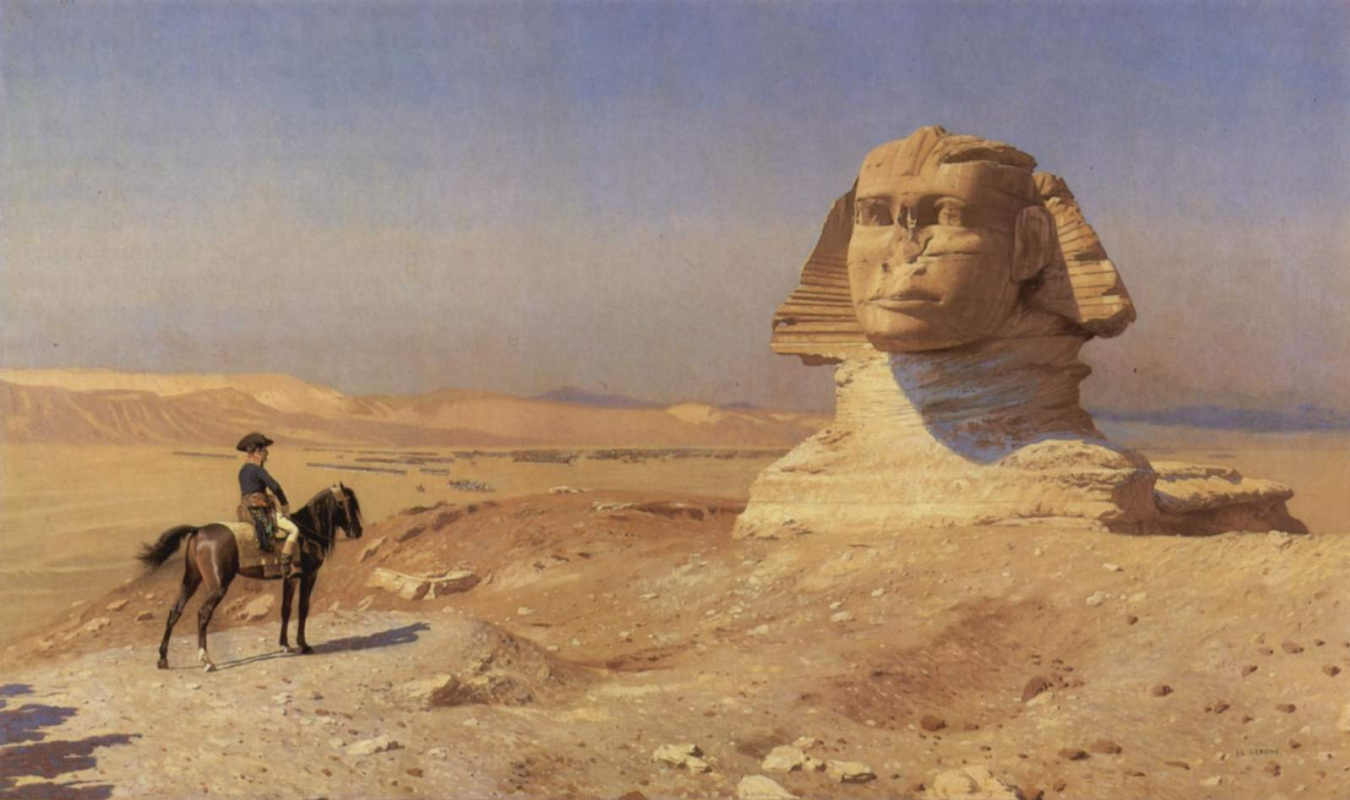

Sphinx

1867

Napoleonic plans and world exhibitions

Until the 19th century, Western artists had a very limited understanding of the oriental countries and their inhabitants. They never left Europe, but they learnt about the mysterious, cruel, and hot Orient from Biblical legends and literary sources. For example, before his trip to Africa, Eugène Delacroix tried to paint exotic subjects several times (1, 2): to create typical images and details, he drew profiles from the coins of the Ancient East, studied engravings on Delhi palaces and Mongolian miniatures. Why shouldn’t the Assyrian king be like the ancient Greeks or Persian rulers?Things began to change at the turn of the 18th century, when General Napoleon Bonaparte set off for the Egyptian campaign. Thousands of scholars and artists also went on this campaign, and after a few years they have compiled all the information about the country in the multivolume edition "Description of Egypt." The mythologization of the Orient began with this military (rather unsuccessful) expedition: the more facts about the monuments of the past and about the modern life of the African state became known, the more they incited imagination and the faster they grew into speculation. Writers and artists, travellers and gamblers of fashionable things were obsessed with the East.

But only a few desperate travellers could see everything with their own eyes. The situation changed in the middle of the century, when in London, and later in Paris, World Exhibitions were organized. These grandiose demonstrations of industrial, agricultural and cultural achievements, unprecedentedly beneficial for the organizers, annually attracted millions of visitors to specially built pavilions. Starting with the demonstration of costumes and household items of the Oriental peoples, non-European pavilions eventually grew to the stylized settlements: the Senegalese village at the 1878 World Exhibition or Cairo Street at the 1889 World Exhibition.

The materials on all French colonies were prepared for the 1900 exhibition in Paris: photographs, maps, dictionaries, household items and works of local art. And especially for the London exhibition, which was dedicated to the Zulus, 13 representatives of the tribe were brought to England to demonstrate their usual activities and religious rituals to Europeans for a year and a half.

This vast and long lasting passion for oriental exoticism had a different effect on individual artists and entire artistic movements, their aesthetics and painting techniques.

The materials on all French colonies were prepared for the 1900 exhibition in Paris: photographs, maps, dictionaries, household items and works of local art. And especially for the London exhibition, which was dedicated to the Zulus, 13 representatives of the tribe were brought to England to demonstrate their usual activities and religious rituals to Europeans for a year and a half.

This vast and long lasting passion for oriental exoticism had a different effect on individual artists and entire artistic movements, their aesthetics and painting techniques.

View of Tangier with figures

1853, 47.2×56.4 cm

From oriental scenery to oriental colours

Tiles, baths, dark-skinned servants, saturated small patterns, naked odalisques on silk striped bedspreads, turbans with precious stones — these exotic elements were found in the paintings of European artists during the Renaissance and Baroque . They were more of a fantasy, stylization and identification marks of the nationality of the ancient heroes. The Rococo aesthetics had its own way to playfully pack frivolous scenes into chaste packaging: if you painta naked blonde and call her the Greek goddess or Odalisque, the nude ceases to be obscenity.

Even the eminent classicist Dominic Ingres had oriental motifs and subjects only as the elements of scenery. His bathers in Turkish baths, sleeping odalisques, languid harem inhabitants do not differ much from the heroines of Greek myths. They have the same faces and forms.

The idea of the East as a passionate, wild, sensual, real world, which is not spoiled by civilization, appears in the art of Romanticism artists. Contrasting the cold rationality, orderliness, deceit of the modern Western world with oriental immediacy, fury and impulsivity, romantics dream and rave about the Orient.

Eugène Delacroix went to Africa and filled his albums with watercolour sketches, providing them with brief notes. Under the hot, exposing sun of Morocco and Algeria, he opened up new colours, bright shadows and revealed moving reflexes: each colour was reflected in the neighbouring one.

The orientalism of the Romantic artists is not limited to the choice of subjects and covers the compositional dynamics, bold and sweeping brushwork, curved

bodies and fighting animals, voluminous draperies and, of course, pure and saturated colours.

It is interesting to compare the orientalist paintings by Eugène Delacroix with the oriental genre paintings by the famous salon artist Jean-Léon Gérôme. He visited Istanbul and Egypt, made hundreds of ethnographic sketches of costumes and animals. But these observations only affected the subjects of the massive cycle of oriental paintings by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1, 2, 3), while the compositions of his works were still static, and the pictorial manner was still academic.

bodies and fighting animals, voluminous draperies and, of course, pure and saturated colours.

It is interesting to compare the orientalist paintings by Eugène Delacroix with the oriental genre paintings by the famous salon artist Jean-Léon Gérôme. He visited Istanbul and Egypt, made hundreds of ethnographic sketches of costumes and animals. But these observations only affected the subjects of the massive cycle of oriental paintings by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1, 2, 3), while the compositions of his works were still static, and the pictorial manner was still academic.

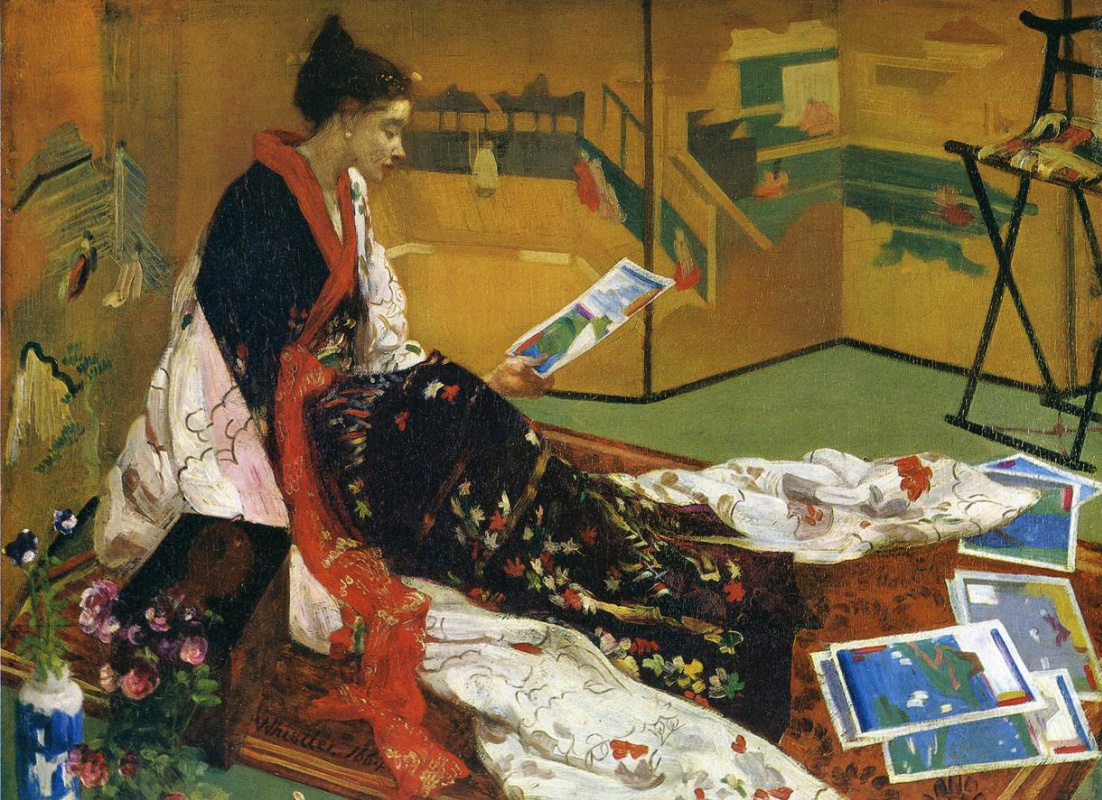

Caprice in purple and gold: the Golden screen

1864, 50.2×68.7 cm

Japaneseism – a new orientalism

None of the impressionist and post-impressionist artists has been to Japan. Until the middle of the 19th century, this country was closed, having neither diplomatic, nor trade ties. Earlier, they had not known Japan in Europe, they did not study it — neither its myths, nor literary fantasies, nor scientific works, nor traditional relationship. Young European travellers to Japan were pioneers. Therefore, the first information about the country fell suddenly on the Europeans, allowing them to draw conclusions and study the new aesthetics independently, without art historians, salon judges and public opinion. And this was the first time that the pictorial tradition of the Occident was influenced by the pictorial tradition of the Orient. This was the first contact that bypassed science and literature.In Parisian shops that sold Japanese wonders, ukiyo-e engravings appeared — at first these colour pictures were used to wrap porcelain, but young artists examined them very quickly and discovered an artistic world that was consonant with the one they were upholding. These were pictures of everyday life, minor episodes with no special subjects. Simplified forms, spots of pure colour and lack of volume, figures cut off by the edge of the paper, the centre of the composition always shifted to the side — all these elements of Japanese aesthetics would become a revelation to the impressionist artists. And this was the confirmation of the appropriateness of their search.

Impressionists collected Japanese prints. The series of paintings by Monet and Cézanne, dedicated to a certain object (Monet's haystacks and water lilies, Cézanne's Mont Sainte-Victoire) was a Japanese technique. Dega’s unusual foreshortenings and compositions cut in the foreground were the result of the Japanese influence. Stains of pure saturated colour in Van Gogh’s paintings and in the lithographs by Toulouse-Lautrec are taken from Hiroshige и Hokusai.

Even the boom of lithographic albums in Paris in the 1890s was a kind of attempt to follow the experience of Japanese lithography , applying it to French everyday life. Ambroise Vollard commissioned the cycles of lithographs to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and the artists of the Nabi group. The intimate interiors by Édouard Vuillard with lampshades and kitchen utensils, memories of Maurice Denis’s first love, "Some Scenes of Parisian Life" Pierre Bonnard were inspired by the endless Japanese road views of Mount Fuji and Tokaido Station.

Even the boom of lithographic albums in Paris in the 1890s was a kind of attempt to follow the experience of Japanese lithography , applying it to French everyday life. Ambroise Vollard commissioned the cycles of lithographs to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and the artists of the Nabi group. The intimate interiors by Édouard Vuillard with lampshades and kitchen utensils, memories of Maurice Denis’s first love, "Some Scenes of Parisian Life" Pierre Bonnard were inspired by the endless Japanese road views of Mount Fuji and Tokaido Station.

Kairouan

29×22 cm

Back to Africa

The last artist to seek the earthly paradise in the Orient was probably Paul Gauguin. He still hoped to find the real world untouched by civilization by going as far as possible from France, to its remotest colony. Gauguin travelled to Tahiti.The subsequent cultural interaction between European and Oriental countries can hardly be included in the concept of orientalism. That was a dialogue and exchange. The relations of the conqueror and the subjugated colony would not soon come close to talking on equal terms: Europeans still missionize and civilize, but behind the simple, "unimpaired" life of the conquered peoples, they increasingly notice the natural balance and wisdom lost by the Europeans over the centuries of rapid development. At the early 20th century, ethnographic exhibitions and museums in London, Munich and Paris no longer surprise spectators with shamanistic rituals and outlandish household items. A new generation of artists, future avant-garde artists, began to discover African art — simple, powerful, free from unnecessary detail and possessing magnetic energy.

After their visit to Morocco and Egypt, both Henri Matisse and Paul Klee, brought back to Europe not the descriptive sketches, but new creative methods, colours and ways of depicting reality. Мaurits Escher did not even have to leave Europe for Oriental impressions: he just looked at the ancient mosaic

on the walls and floors of the Spanish Alhambra and came up with a geometrical and kaleidoscopic "Metamorphoses" series.

The first Cubist period in the work of Pablo Picasso is called African. The 26-year-old artist visited an ethnographic exhibition in Paris in 1907, and experienced a kind of professional insight. Simple, roughly carved, monumental stone figures give rise to much stronger and deeper emotions compared to an aesthetic, refined, theory-rich and overloaded with detail European art. And Picasso began to simplify. He started to eliminate all unnecessary details from faces and figures, turning them into primitive masks.

After 10—20 years, Alberto Giacometti in his Paris workshop began to sculpt narrow, thinned bust profiles and faces, that were reduced to one visible surface. He realized once that it were the flat African masks that enable to convey the truly correct vision of reality, and not the Greco-Roman sculptures modelling the volume. That is exactly how we see life — every time only the one side of it. And at this moment, other angles simply do not exist.

In the 20th century, artists went eastward again, mentally and sometimes physically, with their suitcases, but they were looking for a special view of the world. With a sense of some backwardness and civilized inferiority of themselves, and with the same hope to find the lost paradise.

In the 20th century, artists went eastward again, mentally and sometimes physically, with their suitcases, but they were looking for a special view of the world. With a sense of some backwardness and civilized inferiority of themselves, and with the same hope to find the lost paradise.

Eastern sketch. The Arab camp

1883, 19.7×34.3 cm

Orientalism: a Crib

The artists whose works feature the elements of Orientalism:

Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme, Dominique Ingres, Auguste Renoir, Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jean Édouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard, Félix Vallotton, Maurice Denis, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, August Macke, John Singer Sargent, James Whistler, Albert Marquet, Alberto Giacometti, Vasily Vereshchagin, Zinaida Serebryakova, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin.You are an expert if:

— you can distinguish the artistic oriental props in the picture like colourful bedspreads and turbans from real oriental impressions, even when the subjectof the picture is just a struggle of two enraged horses;

— you recognize not only the famous "Algerian Women" by Eugène Delacroix, but also at least a couple of the 15 cubist variations of "The Algerian Women" by Pablo Picasso;

— you look at Tilda Swinton walking along the night Tangier in the "Only Lovers Left Alive" movie by Jim Jarmusch and remember the Matisse’s Кasbah.

You are a layman if:

— you only notice the oriental influence in those paintings where a harem, Arabs in white burnouses or the glitter of a Turkish sabre are definitely visible;— you are sure that Western art has passed an independent path, which was in no way connected with politics, wars and diplomatic treaties;

— you consider oriental art primitive, and European, highly developed. Well, in fact, you can’t be a 200-year-old colonizer!

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Title illustration: Eugène Delacroix. The Lion Hunt. 1858