Creative work is something personal, even intimate. However, in art history, there were quite a number of instances when artists did not only work in co-operation, but lived side by side. Arthive will give an overview of some European art colonies where painters and sculptors admired beautiful landscapes, drank, debated, and in the meantime, created masterpieces, styles, and artistic movements.

There is hardly a place an artist would not choose to live in: metropolitan districts, deep countryside, beaches, riverbanks and lakesides, a deserted monastery and a wealthy art patron’s manor.

Where: The village of Barbizon in the Fontainebleau Forest near Paris

When: 1830s—1860s

Notable residents: Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Narcisse Díaz, Jules Dupré, Constant Troyon, Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet

More detail: It was love the whole thing started with. Théodore Rousseau fell in love with Augustine, George Sand’s adopted daughter. The novelist approved of the feeling and even promised a dowry of 100,000 francs, and the wedding was on the horizon. But there was George Sand’s own daughter Solange, and she hated the idea of her family losing such a sum. So she spread rumours that Augustine loved another man. Heartbroken, Rousseau left for Barbizon, deep in the countryside, where he had painted en plein air many a time before. After 1847, he never took up residence anywhere else.

Soon, Rousseau was joined by Millet with his big family, and by other like-minded colleagues. Realistic landscape and rural scenes became the main subject of their art. The painters stayed in cottages or at the Auberge Ganne (Ganne's Inn). The innkeeper even had to add an outbuilding to house the artists' studios (the Barbizonians made sketches and studies outdoors, of course, but finished their work in their studios). Père-Ganne always wanted pre-payment: he quickly realised that most painters who flocked to the place were far from well-off.

Millet would get up early, do some farmwork first, and only then take the paintbrush. He was very proud of being an ordinary peasant. In Barbizon, artists sought simplicity. In their pictures, they never glamorised peasant’s poverty and toil, and in the evenings, after hours of painting, they had plain soup for supper, with no white table-cover and silverware.

Though the summit of Barbizon’s fame was in the 1850s, in later years, artists still frequented the place in search of inspiration. Besides, they had another reason for coming there. It was the time when landscapes were becoming popular with art collectors, and all painters took to this genre. Fontainebleau attracted visitors from all over Europe, and even from America. In 1872, in Barbizon, there were 300 residents altogether, of them 100 painters, and 147 peasants, the central figures of the scenes so sought after.

Impressionists (1, 2), too, visited the Fontainebleau Forest, but never stayed long: they were interested in light and did not find enough of it in the forest.

This is how Renoir, who, in his penniless years, used to walk to Fontainebleau from Paris, later remembered the Barbizonians, ‘Rousseau amazed me, and Daubigny also; but I realized immediately that the really great painter was Corot. His work is for all time. Like Vermeer of Delft, he didn’t paint just for his own day. I loathed Millet. His sentimental peasants made me think of actors dressed up to look like peasants. … And in Diaz’s painting, you can almost smell the mushrooms, dead leaves and moss.'

The Barbizonians would be called the forerunners of Impressionism. Millet’s images would later be interpreted by Van Gogh (1, 2, 3) and Dali (1, 2, 3).

When: 1830s—1860s

Notable residents: Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, Narcisse Díaz, Jules Dupré, Constant Troyon, Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet

More detail: It was love the whole thing started with. Théodore Rousseau fell in love with Augustine, George Sand’s adopted daughter. The novelist approved of the feeling and even promised a dowry of 100,000 francs, and the wedding was on the horizon. But there was George Sand’s own daughter Solange, and she hated the idea of her family losing such a sum. So she spread rumours that Augustine loved another man. Heartbroken, Rousseau left for Barbizon, deep in the countryside, where he had painted en plein air many a time before. After 1847, he never took up residence anywhere else.

Soon, Rousseau was joined by Millet with his big family, and by other like-minded colleagues. Realistic landscape and rural scenes became the main subject of their art. The painters stayed in cottages or at the Auberge Ganne (Ganne's Inn). The innkeeper even had to add an outbuilding to house the artists' studios (the Barbizonians made sketches and studies outdoors, of course, but finished their work in their studios). Père-Ganne always wanted pre-payment: he quickly realised that most painters who flocked to the place were far from well-off.

Millet would get up early, do some farmwork first, and only then take the paintbrush. He was very proud of being an ordinary peasant. In Barbizon, artists sought simplicity. In their pictures, they never glamorised peasant’s poverty and toil, and in the evenings, after hours of painting, they had plain soup for supper, with no white table-cover and silverware.

Though the summit of Barbizon’s fame was in the 1850s, in later years, artists still frequented the place in search of inspiration. Besides, they had another reason for coming there. It was the time when landscapes were becoming popular with art collectors, and all painters took to this genre. Fontainebleau attracted visitors from all over Europe, and even from America. In 1872, in Barbizon, there were 300 residents altogether, of them 100 painters, and 147 peasants, the central figures of the scenes so sought after.

Impressionists (1, 2), too, visited the Fontainebleau Forest, but never stayed long: they were interested in light and did not find enough of it in the forest.

This is how Renoir, who, in his penniless years, used to walk to Fontainebleau from Paris, later remembered the Barbizonians, ‘Rousseau amazed me, and Daubigny also; but I realized immediately that the really great painter was Corot. His work is for all time. Like Vermeer of Delft, he didn’t paint just for his own day. I loathed Millet. His sentimental peasants made me think of actors dressed up to look like peasants. … And in Diaz’s painting, you can almost smell the mushrooms, dead leaves and moss.'

The Barbizonians would be called the forerunners of Impressionism. Millet’s images would later be interpreted by Van Gogh (1, 2, 3) and Dali (1, 2, 3).

Masterpieces painted in Barbizon:

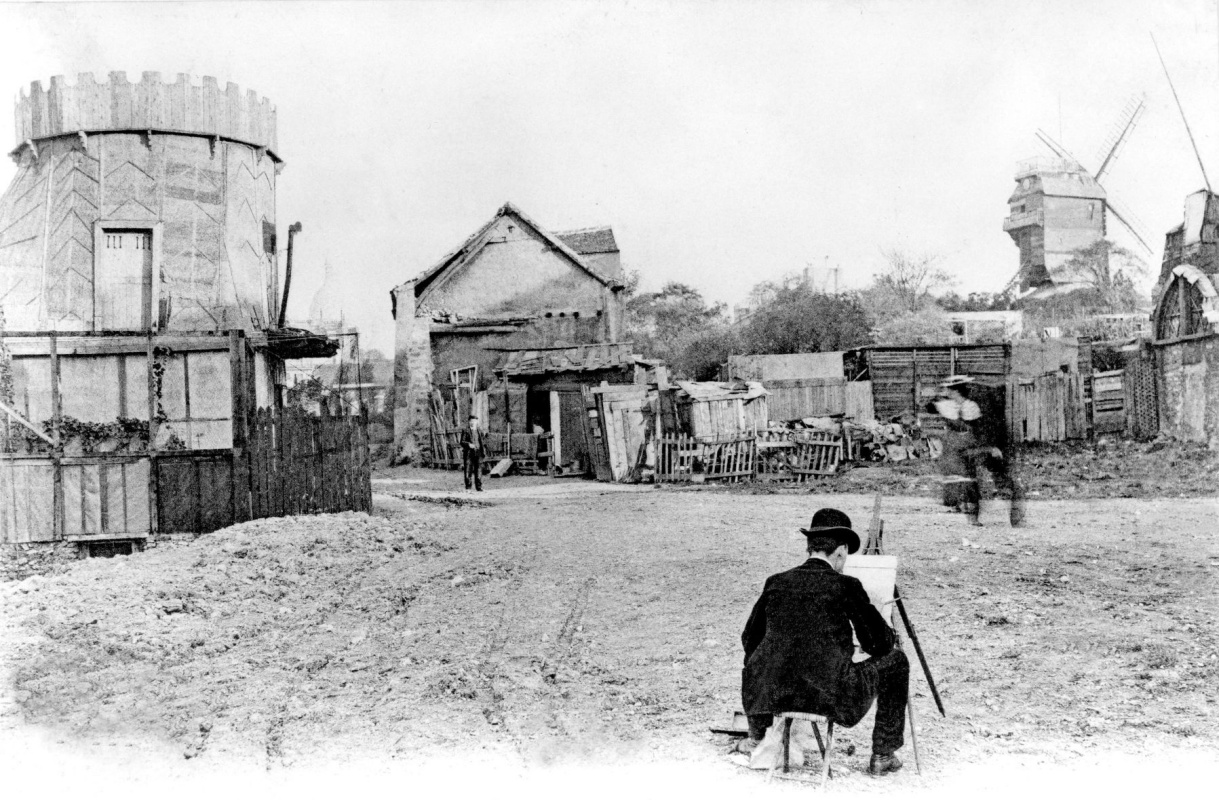

A painter working in Montmartre, early 20th century. (Credit: huffingtonpost.com)

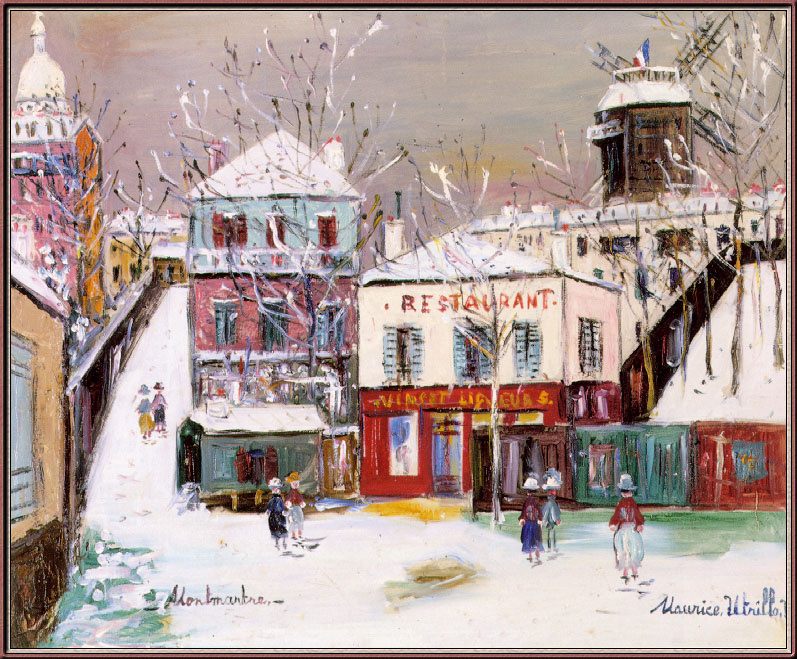

Where: The hill of Montmartre, the highest point in Paris

When: 1871—1914

Notable residents: Auguste Renoir, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Suzanne Valadon, Maurice Utrillo, Amedeo Modigliani, Théodore Rousseau, Paul Signac, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck

More detail: A suburb of Paris, a village surrounded by a big city, Montmartre became a legend and the prototype for a number of similar quarters where artists lodged, drank alcohol, had fun, debated, and painted. In the second half of the 19th century, when artists started settling down there, it was a poorly civilised area with plots of vegetables, water wells, fields that belonged to no-one and were used for grazing cows and picking grass for rabbits. Fiacres rarely appeared there, for it was too long a way to go uphill, and getting to Paris (an hour’s walk) could turn out to be quite a trek. Impressionists started migrating to this wild territory right after the Franco-Prussian War. Living there was cheap, and the place looked like the countryside: picturesque views, peace, and freedom.

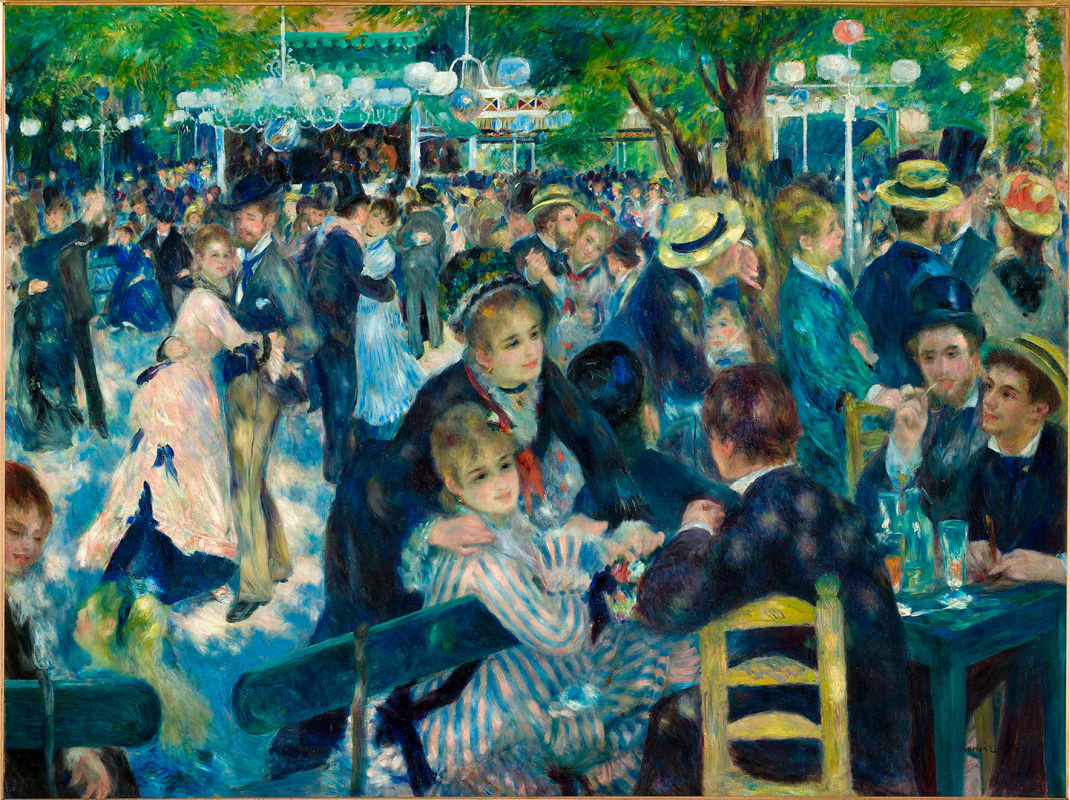

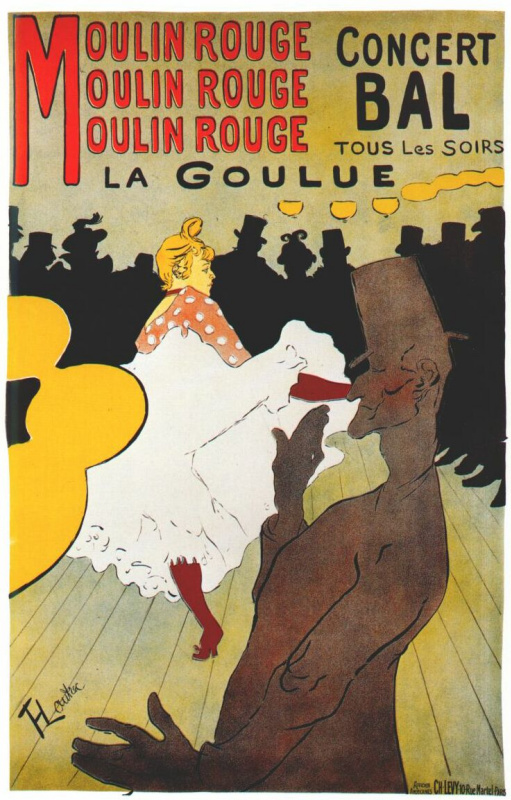

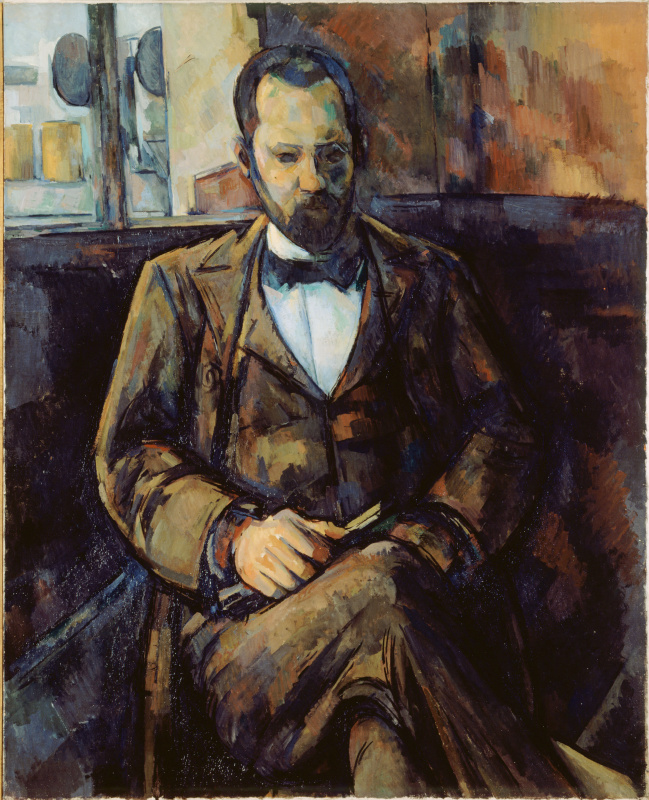

Auguste Renoir moved to Montmartre when he decided to paint the large, many-figured outdoor composition Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette. Among his other occupations, there was wiping the noses of Montmartre kids who sauntered around unsupervised, being in love, looking for models among young sewing-maids and laundry-girls, and even being on friendly terms with street thugs. Later, he dwelt for a long time in Allée de Brouillards (Avenue of Mists), also in Montmartre, where his own children could get fresh air, sneak to the neighbours' garden for pears, and have new milk taken every day from the woman next door. Almost everything painted by Toulouse-Lautrec took place in Montmartre: circuses, cabarets, dances, singers, prostitutes, clowns. He painted Aristide Bruant, who, by night, would call dressed-up bourgeois customers at Le Mirliton pigs and whores, and in the mornings, would race about Montmartre on his bicycle. Cézanne had changed a dozen studios in Paris before finding the last one in Montmartre, at the Villa des Arts. Here, he portrayed Ambroise Vollard — and drove him to frenzy with innumerable sitting sessions (which were, by different estimates, 80 to over 100). At the foot of Montmartre, those who would become Impressionists, creators of new art, gathered at the Café Guerbois, and later, at the Nouvelle Athènes.

By the 20th century, Montmartre was a Bohemian, poverty-stricken, artistic, avant-garde , hungry district. Along with the Villa des Arts (which was actually a sort of hostel with cheap studios, not a villa), another focal point for artists was the Villa des Fusains, formerly the pavilions of the Exposition Universelle. It was to be demolished, but a doctor who patronised art redecorated the building for Modigliani and other destitute avant-garde artists, fitted it with simplest furniture, and turned the ground floor into a gallery. Modigliani’s interest at that time was carving wooden sculptures. By night, he would steal wooden sleepers from a railway, and by day, used them as material for his work.

Young Pablo Picasso must have had no idea of the iconic status of the place. It was at the time when Montmartre had just started becoming a legend, that he moved there, into the Bateau-Lavoir. The house was a sort of hostel, quite a shabby one: no electricity, only one water-tap, and a single toilet for the five-storeyed building. At different times, the Bateau-Lavoir was home for Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin, for Spanish and Italian communities. Here, Fauvism and Futurism took shape, and in front of the cabaret Lapin Agile, a big bowl of soup was regularly offered to hungry artists. But they would never hesitate to leave Montmartre the moment they earned their first big money. The one who stayed longest was Maurice Utrillo — he kept painting the streets of the renowned hill all his life.

When: 1871—1914

Notable residents: Auguste Renoir, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Suzanne Valadon, Maurice Utrillo, Amedeo Modigliani, Théodore Rousseau, Paul Signac, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck

More detail: A suburb of Paris, a village surrounded by a big city, Montmartre became a legend and the prototype for a number of similar quarters where artists lodged, drank alcohol, had fun, debated, and painted. In the second half of the 19th century, when artists started settling down there, it was a poorly civilised area with plots of vegetables, water wells, fields that belonged to no-one and were used for grazing cows and picking grass for rabbits. Fiacres rarely appeared there, for it was too long a way to go uphill, and getting to Paris (an hour’s walk) could turn out to be quite a trek. Impressionists started migrating to this wild territory right after the Franco-Prussian War. Living there was cheap, and the place looked like the countryside: picturesque views, peace, and freedom.

Auguste Renoir moved to Montmartre when he decided to paint the large, many-figured outdoor composition Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette. Among his other occupations, there was wiping the noses of Montmartre kids who sauntered around unsupervised, being in love, looking for models among young sewing-maids and laundry-girls, and even being on friendly terms with street thugs. Later, he dwelt for a long time in Allée de Brouillards (Avenue of Mists), also in Montmartre, where his own children could get fresh air, sneak to the neighbours' garden for pears, and have new milk taken every day from the woman next door. Almost everything painted by Toulouse-Lautrec took place in Montmartre: circuses, cabarets, dances, singers, prostitutes, clowns. He painted Aristide Bruant, who, by night, would call dressed-up bourgeois customers at Le Mirliton pigs and whores, and in the mornings, would race about Montmartre on his bicycle. Cézanne had changed a dozen studios in Paris before finding the last one in Montmartre, at the Villa des Arts. Here, he portrayed Ambroise Vollard — and drove him to frenzy with innumerable sitting sessions (which were, by different estimates, 80 to over 100). At the foot of Montmartre, those who would become Impressionists, creators of new art, gathered at the Café Guerbois, and later, at the Nouvelle Athènes.

By the 20th century, Montmartre was a Bohemian, poverty-stricken, artistic, avant-garde , hungry district. Along with the Villa des Arts (which was actually a sort of hostel with cheap studios, not a villa), another focal point for artists was the Villa des Fusains, formerly the pavilions of the Exposition Universelle. It was to be demolished, but a doctor who patronised art redecorated the building for Modigliani and other destitute avant-garde artists, fitted it with simplest furniture, and turned the ground floor into a gallery. Modigliani’s interest at that time was carving wooden sculptures. By night, he would steal wooden sleepers from a railway, and by day, used them as material for his work.

Young Pablo Picasso must have had no idea of the iconic status of the place. It was at the time when Montmartre had just started becoming a legend, that he moved there, into the Bateau-Lavoir. The house was a sort of hostel, quite a shabby one: no electricity, only one water-tap, and a single toilet for the five-storeyed building. At different times, the Bateau-Lavoir was home for Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Paul Gauguin, for Spanish and Italian communities. Here, Fauvism and Futurism took shape, and in front of the cabaret Lapin Agile, a big bowl of soup was regularly offered to hungry artists. But they would never hesitate to leave Montmartre the moment they earned their first big money. The one who stayed longest was Maurice Utrillo — he kept painting the streets of the renowned hill all his life.

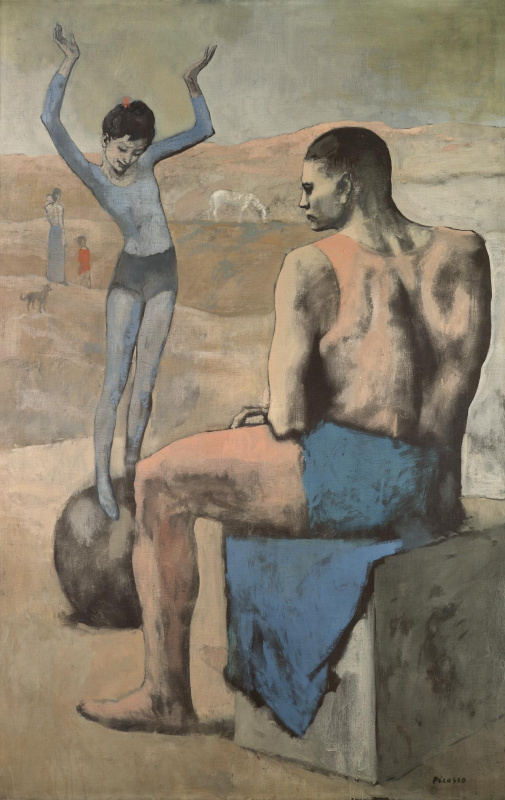

Masterpieces created in Montmartre:

La Ruche in the days of Modigliani. 1918

Where: Paris

When: 1902 — present

Notable residents: Amedeo Modigliani, Marc Chagall, Ossip Zadkine, Chaïm Soutine, Moïse Kisling, Fernand Léger, Max Jacob, Alexander Archipenko, Diego Rivera

More detail: The curious name of the famous Parisian phalanstery La Ruche (the French for ‘beehive') is due to the shape of the building and the honeycomb-like arrangement of artists' studios and rooms.

In the early 20th century, the cultural life of Paris was changing greatly. Firstly, painters, sculptors, and writers were all moving from Montmartre to Montparnasse, the latter thus becoming a new artistic centre of the French capital. Secondly, a lot of immigrant artists, quite a number of them from Russia, surged into the cosmopolitan city. Mostly, they were those not allowed into Russian educational institutions because of the Jewish origin. Cash-strapped, often having nothing to buy food for, the newcomers found La Ruche a perfect abode.

The honeycomb-like house appeared in the Passage Danzig, in the south west of Paris, due to the sculptor Alfred Boucher and the architect Gustave Eiffel. The latter designed a rotunda for the Great Exposition of 1900 in Paris. Then, Boucher acquired it, relocated to Montparnasse, and made it a residential compound for artists and writers. In 1902, La Ruche opened its door for the first lodgers. The accommodation cost next to nothing, and no tenants were evicted for falling behind in paying the rent. To be fair, the living conditions in La Ruche left much to be desired, for, originally, it had not been intended to be a lodging place. Typically, the dwellers used the tiny rooms they lived in as their studios. The daytime was for work, and then painters and sculptors proceeded to the improvised dinner-table the Russian painter Marie Vassilieff volunteered to organise. For a token price of 60 centimes, they could refresh themselves with some hot broth, bread, and meat, have a cup of coffee, and spend the evening in an interesting conversation with people who shared their views.

Chagall came to Paris in May 1911, and lived in La Ruche four years. In the picture Half Past Three, he showed a scene from his everyday life: his friends often visited the painter in his studio for a good chat or a glassful.

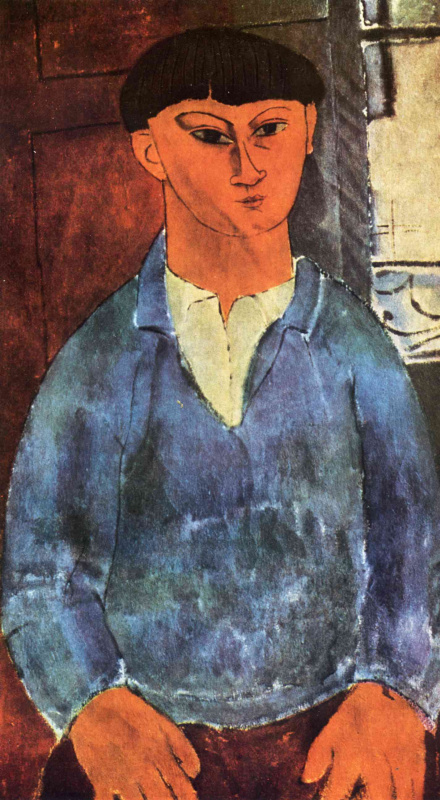

While living in La Ruche, Modigliani became a local hero because of his fondness for binges. However, he somehow managed to work a lot and often portrayed his colleagues living beneath the same roof — Kisling, for example.

In the days of World War II, La Ruche fell to desolation, but, luckily, it was restored later. And nowadays, the legendary Eiffel’s creation is inhabited by painters and sculptors again. It is not easy, though, to rent a room there: the accommodation costs pretty high, and each prospective tenant should be approved by a special committee.

When: 1902 — present

Notable residents: Amedeo Modigliani, Marc Chagall, Ossip Zadkine, Chaïm Soutine, Moïse Kisling, Fernand Léger, Max Jacob, Alexander Archipenko, Diego Rivera

More detail: The curious name of the famous Parisian phalanstery La Ruche (the French for ‘beehive') is due to the shape of the building and the honeycomb-like arrangement of artists' studios and rooms.

In the early 20th century, the cultural life of Paris was changing greatly. Firstly, painters, sculptors, and writers were all moving from Montmartre to Montparnasse, the latter thus becoming a new artistic centre of the French capital. Secondly, a lot of immigrant artists, quite a number of them from Russia, surged into the cosmopolitan city. Mostly, they were those not allowed into Russian educational institutions because of the Jewish origin. Cash-strapped, often having nothing to buy food for, the newcomers found La Ruche a perfect abode.

The honeycomb-like house appeared in the Passage Danzig, in the south west of Paris, due to the sculptor Alfred Boucher and the architect Gustave Eiffel. The latter designed a rotunda for the Great Exposition of 1900 in Paris. Then, Boucher acquired it, relocated to Montparnasse, and made it a residential compound for artists and writers. In 1902, La Ruche opened its door for the first lodgers. The accommodation cost next to nothing, and no tenants were evicted for falling behind in paying the rent. To be fair, the living conditions in La Ruche left much to be desired, for, originally, it had not been intended to be a lodging place. Typically, the dwellers used the tiny rooms they lived in as their studios. The daytime was for work, and then painters and sculptors proceeded to the improvised dinner-table the Russian painter Marie Vassilieff volunteered to organise. For a token price of 60 centimes, they could refresh themselves with some hot broth, bread, and meat, have a cup of coffee, and spend the evening in an interesting conversation with people who shared their views.

Chagall came to Paris in May 1911, and lived in La Ruche four years. In the picture Half Past Three, he showed a scene from his everyday life: his friends often visited the painter in his studio for a good chat or a glassful.

While living in La Ruche, Modigliani became a local hero because of his fondness for binges. However, he somehow managed to work a lot and often portrayed his colleagues living beneath the same roof — Kisling, for example.

In the days of World War II, La Ruche fell to desolation, but, luckily, it was restored later. And nowadays, the legendary Eiffel’s creation is inhabited by painters and sculptors again. It is not easy, though, to rent a room there: the accommodation costs pretty high, and each prospective tenant should be approved by a special committee.

Masterpieces created in La Ruche:

Yellow house

September 1888, 91.5×72 cm

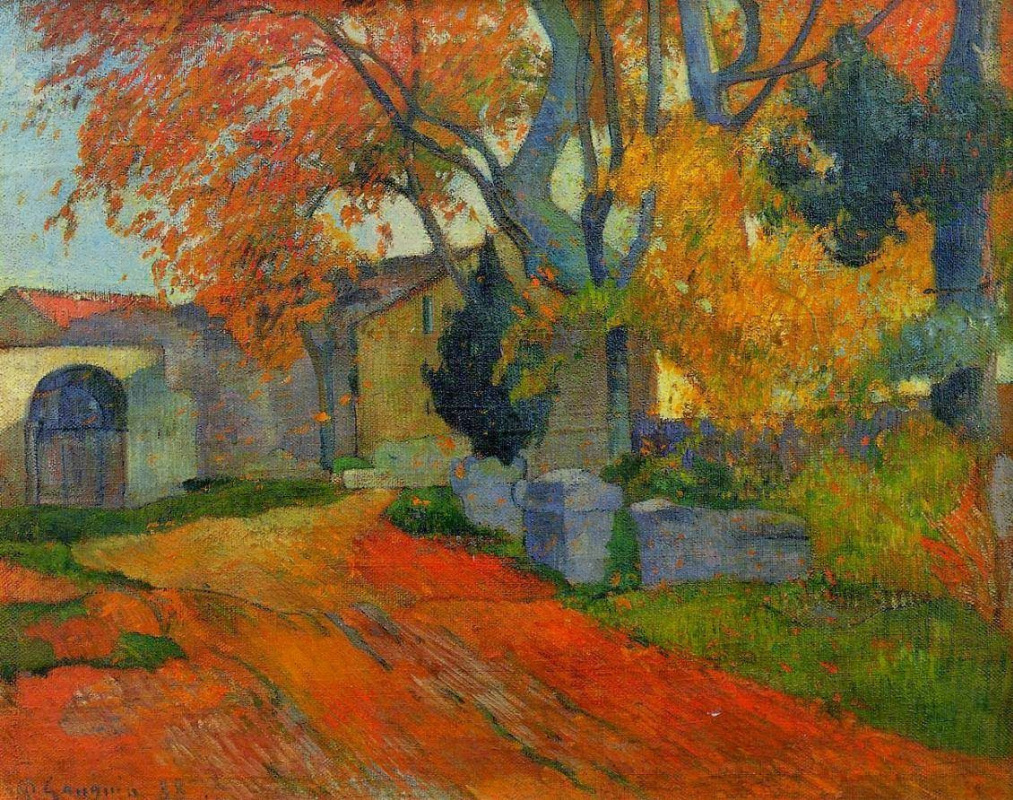

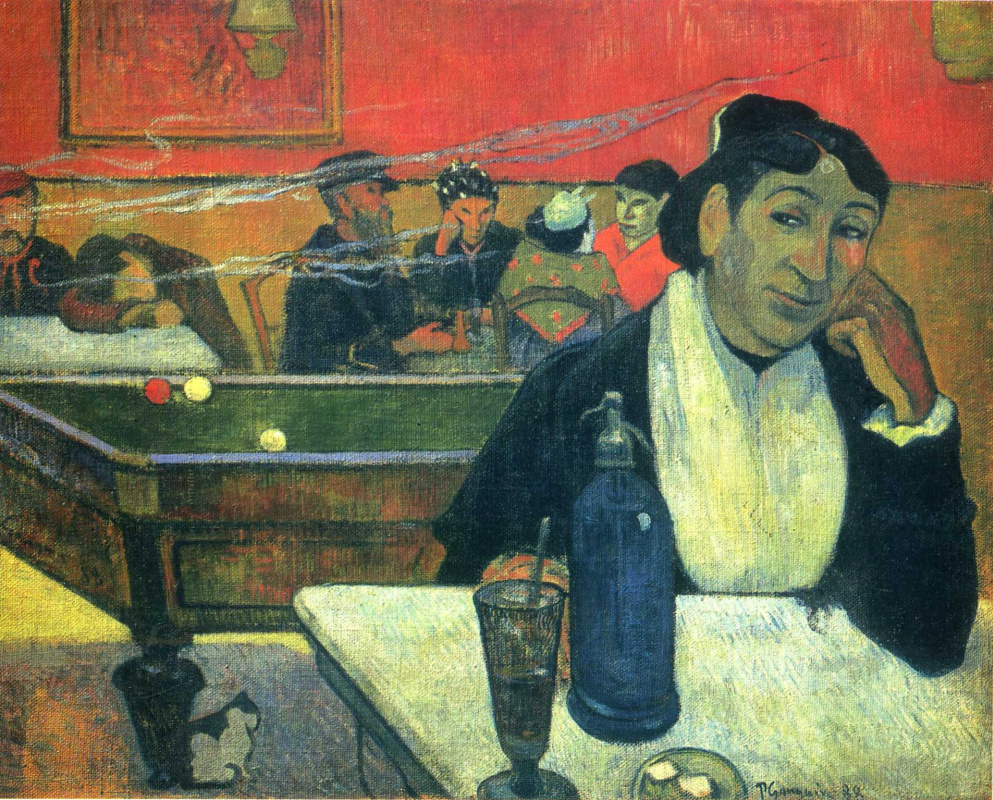

Where: Arles (Provence, France)

When: 1888

Notable residents: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin

More detail: Actually, this commune remained but a dream. It existed for some weeks and only numbered two members, but it did become a landmark in art history.

In February 1888, Van Gogh left Paris for the sunshine of the south where he hoped to find better life and picturesque nature. Exhausted after a hard winter, he did not only long for new inspiration, but wanted to regain his health. Vincent expected to be joined by Gauguin soon, who was leading a tedious life in Brittany and suffered from various maladies, too. His arrival was the first stage of Van Gogh’s ambitious plan to arrange in the South a commune of artists, a refuge, ‘a pied-à-terre which, when people were exhausted, could be used to provide a rest in the country for poor Paris cab-horses.' Vincent hoped that, after a short time, his brother Theo, Émile Bernard, Georges Seurat, and Charles Laval would join them. Van Gogh revered Gauguin’s talent and declared him the Head of the Southern Studio.

The day before Gauguin came to Arles, Vincent rented a small two-storeyed house and showed great enthusiasm furnishing it. He wrote to Theo about the Yellow House, ‘From the start, I wanted to arrange the house not just for myself but in such a way as to be able to put somebody up. <…> For putting somebody up, there’ll be the prettiest room upstairs, which I’ll try to make as nice as possible, like a woman’s boudoir, really artistic.'

Gauguin did not share his enthusiasm. He found tiresome the bad weather, lack of money, and never-ending conflicts. In December, he wrote to Bernard, ‘Vincent and I generally agree very little, especially about painting. <…> He is romantic and me, I incline more to a primitive state. From the point of view of colour, he likes the chance effects of impasto in the manner of Monticelli, whereas I detest all that messing about with brushwork and that kind of thing.' Gauguin detested Arles as well, and once called it ‘the dirtiest town in the whole south.' Though Vincent’s idea failed and resulted in the mutilated ear tragedy, the period when they lived and worked side by side turned out to be highly fruitful for both artists.

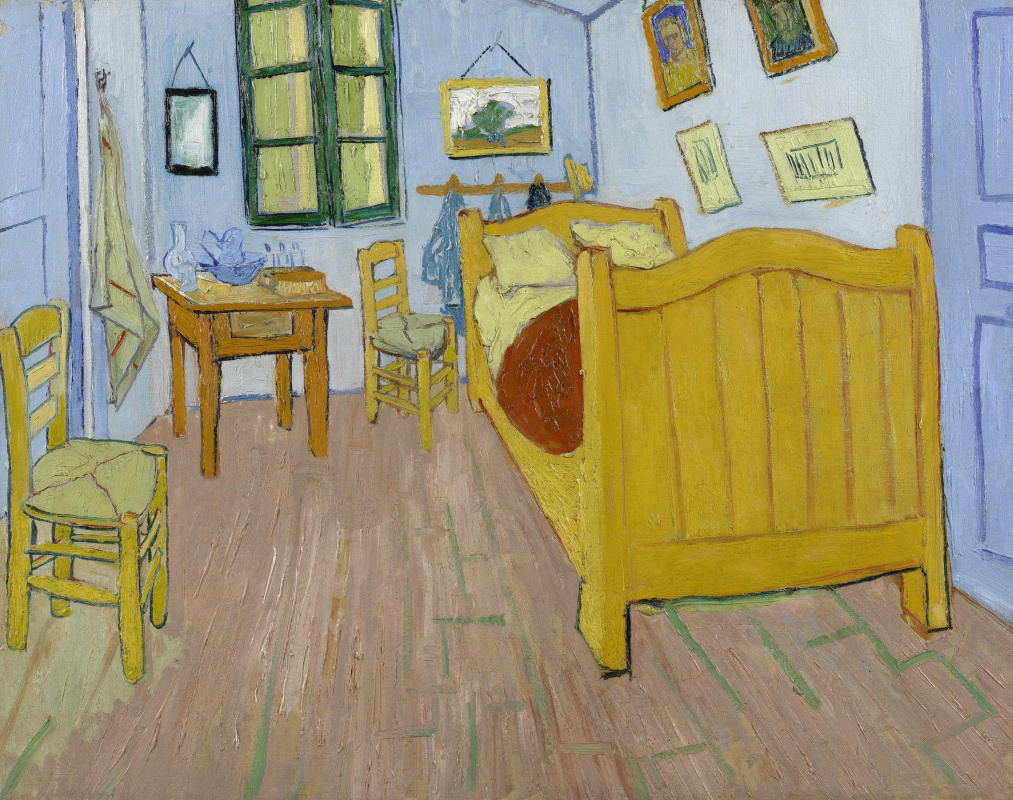

In the Yellow House, Van Gogh lived in the smallest, sparsely furnished room, the picture of which painted by him would become one of the most recognisable images in the world. In Arles, Vincent was enamoured with the yellow colour and ‘sunny flowers.' Awaiting Gauguin’s arrival, he had decorated the walls of the guest room with pictures of sunflowers.

When: 1888

Notable residents: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin

More detail: Actually, this commune remained but a dream. It existed for some weeks and only numbered two members, but it did become a landmark in art history.

In February 1888, Van Gogh left Paris for the sunshine of the south where he hoped to find better life and picturesque nature. Exhausted after a hard winter, he did not only long for new inspiration, but wanted to regain his health. Vincent expected to be joined by Gauguin soon, who was leading a tedious life in Brittany and suffered from various maladies, too. His arrival was the first stage of Van Gogh’s ambitious plan to arrange in the South a commune of artists, a refuge, ‘a pied-à-terre which, when people were exhausted, could be used to provide a rest in the country for poor Paris cab-horses.' Vincent hoped that, after a short time, his brother Theo, Émile Bernard, Georges Seurat, and Charles Laval would join them. Van Gogh revered Gauguin’s talent and declared him the Head of the Southern Studio.

The day before Gauguin came to Arles, Vincent rented a small two-storeyed house and showed great enthusiasm furnishing it. He wrote to Theo about the Yellow House, ‘From the start, I wanted to arrange the house not just for myself but in such a way as to be able to put somebody up. <…> For putting somebody up, there’ll be the prettiest room upstairs, which I’ll try to make as nice as possible, like a woman’s boudoir, really artistic.'

Gauguin did not share his enthusiasm. He found tiresome the bad weather, lack of money, and never-ending conflicts. In December, he wrote to Bernard, ‘Vincent and I generally agree very little, especially about painting. <…> He is romantic and me, I incline more to a primitive state. From the point of view of colour, he likes the chance effects of impasto in the manner of Monticelli, whereas I detest all that messing about with brushwork and that kind of thing.' Gauguin detested Arles as well, and once called it ‘the dirtiest town in the whole south.' Though Vincent’s idea failed and resulted in the mutilated ear tragedy, the period when they lived and worked side by side turned out to be highly fruitful for both artists.

In the Yellow House, Van Gogh lived in the smallest, sparsely furnished room, the picture of which painted by him would become one of the most recognisable images in the world. In Arles, Vincent was enamoured with the yellow colour and ‘sunny flowers.' Awaiting Gauguin’s arrival, he had decorated the walls of the guest room with pictures of sunflowers.

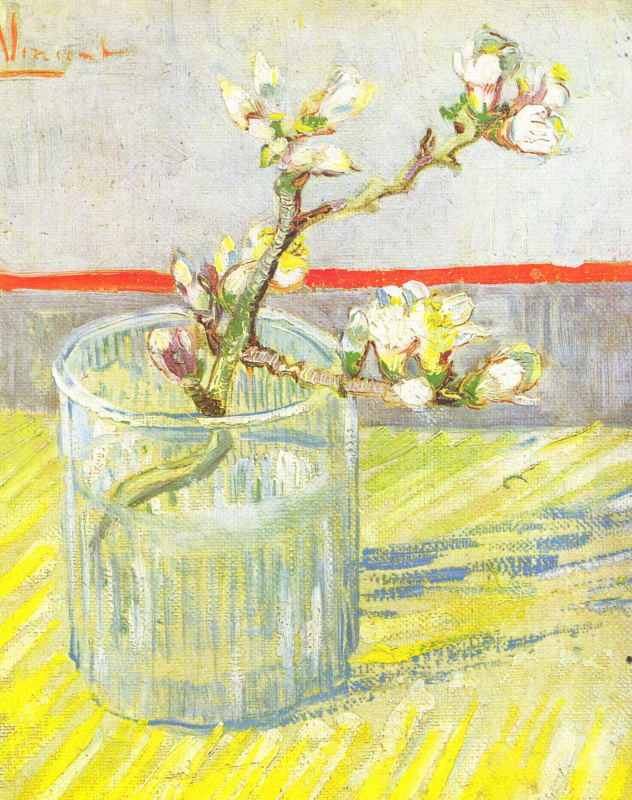

Masterpieces created in Arles:

Nocturne in blue and silver. Chelsea

1871, 60.8×50.2 cm

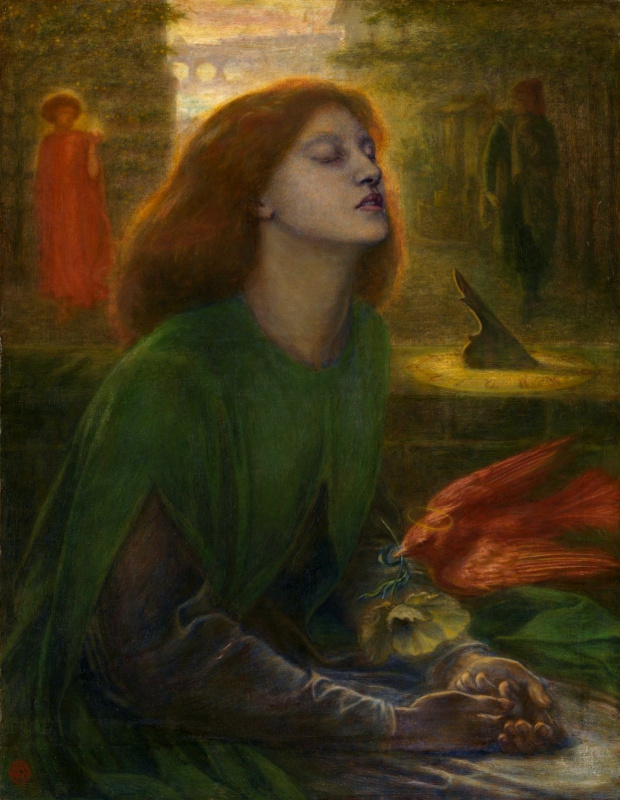

Where: Chelsea, a district in London

When: 1870s—1910s

Notable residents: James Abbott Whistler, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, John Singer Sargent, Walter Greaves and Henry Greaves, Stirling Lee, Theodore Wores, Philip Wilson Steer

More detail: Unlike French artists, who chose Montmartre for it was cheaper to live and work there, their English colleagues took up their residence as close to the River Thames as possible, to enjoy the sight of its flow and the seasonal effects over its surface. Today, Chelsea is one of the most expensive and fashionable parts of London, but in the late 19th century, it was the location of hundreds of studios with common inner yards. People of blatantly scruffy looks used to walk along its streets. They never wore white collars, they smoked clay pipes, and everyone could easily identify them as artists. Some of them were really defiant in their eccentricities: they wore gaudily-coloured clothes, kept exotic animals in their backyards, and saw no shame in having young models as flatmates.

Chelsea became home for James Whistler, and he recommended the district to young painters who had just completed their course in Paris. The Pre-Raphaelites Rossetti and Hunt also anchored themselves there, followed by countless imitators and adherents.

The British people love uniting into clubs, with certain rules, membership, and regular gatherings. Even artists' models had one in Chelsea! So what else should one have expected from the artists who had visited Montmartre and seen the first Impressionist exhibitions — they were but destined to arrive at the idea. The English Arts Club (still existing) opened in 1890. It took several months to make a list of prospective members, find a house with a studio, write the laws (that included an article stipulating the Bohemian status of the club), purchase some old furniture (including a large dinner-table), and make two more studios: for drawing from life, and for working on sketches. And of course, collective evening meals were arranged there, too.

Creating a permanent meeting space, where young artists would have held collective exhibitions, was the club members' primary concern. But in Chelsea, there was absolutely no place for a large group of people to go out to and have a meal, so the dinners were an essential part of the club’s strategy. Ten years later, the Arts Club moved to another building. Then, it already had a billiard and a bowling rooms, and a summer-house in the courtyard. Soon, dancing parties started being held twice a year and became the club’s main source of funding, for all first-rate London musicians, famous actors, poets and writers aspired to get there. The number of members was growing, membership was given to all sort of artists, to urban as well as countryside dwellers, and soon there were more than a hundred and a half of them. But today, their long names mean but little to art lovers and even experts: after Whistler and Hunt died, Chelsea artists went on with their activity but on a far smaller scale. Philip Hook, the author of Breakfast at Sotheby’s, says, ‘ … when Roger Fry looked about for suitable English artists to exhibit in his second great Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912 alongside Picasso, Braque and Matisse, Augustus John refused. Of those chosen — painters such as Spencer Gore, Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Wyndham Lewis — not one was based in Chelsea.' There was no avant-garde art there any longer.

When: 1870s—1910s

Notable residents: James Abbott Whistler, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, John Singer Sargent, Walter Greaves and Henry Greaves, Stirling Lee, Theodore Wores, Philip Wilson Steer

More detail: Unlike French artists, who chose Montmartre for it was cheaper to live and work there, their English colleagues took up their residence as close to the River Thames as possible, to enjoy the sight of its flow and the seasonal effects over its surface. Today, Chelsea is one of the most expensive and fashionable parts of London, but in the late 19th century, it was the location of hundreds of studios with common inner yards. People of blatantly scruffy looks used to walk along its streets. They never wore white collars, they smoked clay pipes, and everyone could easily identify them as artists. Some of them were really defiant in their eccentricities: they wore gaudily-coloured clothes, kept exotic animals in their backyards, and saw no shame in having young models as flatmates.

Chelsea became home for James Whistler, and he recommended the district to young painters who had just completed their course in Paris. The Pre-Raphaelites Rossetti and Hunt also anchored themselves there, followed by countless imitators and adherents.

The British people love uniting into clubs, with certain rules, membership, and regular gatherings. Even artists' models had one in Chelsea! So what else should one have expected from the artists who had visited Montmartre and seen the first Impressionist exhibitions — they were but destined to arrive at the idea. The English Arts Club (still existing) opened in 1890. It took several months to make a list of prospective members, find a house with a studio, write the laws (that included an article stipulating the Bohemian status of the club), purchase some old furniture (including a large dinner-table), and make two more studios: for drawing from life, and for working on sketches. And of course, collective evening meals were arranged there, too.

Creating a permanent meeting space, where young artists would have held collective exhibitions, was the club members' primary concern. But in Chelsea, there was absolutely no place for a large group of people to go out to and have a meal, so the dinners were an essential part of the club’s strategy. Ten years later, the Arts Club moved to another building. Then, it already had a billiard and a bowling rooms, and a summer-house in the courtyard. Soon, dancing parties started being held twice a year and became the club’s main source of funding, for all first-rate London musicians, famous actors, poets and writers aspired to get there. The number of members was growing, membership was given to all sort of artists, to urban as well as countryside dwellers, and soon there were more than a hundred and a half of them. But today, their long names mean but little to art lovers and even experts: after Whistler and Hunt died, Chelsea artists went on with their activity but on a far smaller scale. Philip Hook, the author of Breakfast at Sotheby’s, says, ‘ … when Roger Fry looked about for suitable English artists to exhibit in his second great Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912 alongside Picasso, Braque and Matisse, Augustus John refused. Of those chosen — painters such as Spencer Gore, Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Wyndham Lewis — not one was based in Chelsea.' There was no avant-garde art there any longer.

Masterpieces created in Chelsea:

Where: Rome, Pincian Hill, the Irish Franciscans' abandoned monastery of Sant’Isidoro

When: 1810 — June 1812

Notable residents: Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Franz Pforr, Johann Konrad Hottinger, Josef Wintergerst, Ludwig Vogel, Josef Sutter, Wilhelm von Schadow, Peter von Cornelius

More detail: In 1806, Napoleon in his victorious march through Europe, took control of all Germany. Confusion reigning everywhere, creative minds turned back to the past for ideals once lost. A group of German and Austrian artists, who admired Raphael, Michelangelo, Fra Angelico, Perugino, Dürer, Holbein, and Cranach, united in a community, settled in Italy, and started living a fairyland life.

The founding members of the movement are the two students of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Franz Pforr. Their friendship was due to their shared aversion to Classicist art. Inspired by old canvases in the Belvedere, Vienna, and by the illustrations in the just published book by the Riepenhausen brothers Geschichte der Malerei in Italien (‘History of painting in Italy'), they declared no more cloning of vicious mythological subjects but the return to the purity of ideals in art. They believed one should be guided by Christian doctrines, Renaissance

canons, and examples from history.

In June 1810, the idealists set up an association similar to guilds of old, the Brotherhood of St. Luke (named after the apostle who was considered the patron of painters). After Overbeck was expelled from the Academy for ineptitude, the painters went to Rome, and there, from September 1810, lived in the monastery of Sant’Isidoro founded in the 16th century by Franciscan monks and deserted in the days of Napoleon. The friends were about twenty years old, and, with all the ardour of youth, they plunged into playing their good-old-time game. They wore German national costumes that used to be fashionable in older days, with berets, velvet doublets, collars of lace, capes, sometimes even swords — and the hairstyle alla nazarena (long hair parting in the middle) so as to look like Jesus of Nazareth. It is for that reason that they became known as the Nazarenes. By the way, it was the way Albrecht Dürer, whom they adored, used to wear his hair.

Within the commune, they referred to Overbeck as the Priest and Pforr as the Master. The Nazarenes were humble and pious. They only used cells as studios, never used corpses to study anatomy, never made sketches of nude women models, and sat for each other if there was a need of portraying a character in gorgeous garments. They refused worldly entertainments and social gatherings for work, prayers, walks, and evening debates in the refectory. In a purposely lofty manner, the Nazarenes expressed opinions on each other’s paintings, and discussed philosophy and literature. Their favourite book was Wilhelm Wackenroder’s Herzensergießungen eines kunstliebenden Klosterbruders (‘Outpourings of an Art-Loving Friar'). Following Pforr’s death by tuberculosis in 1812, the friends left the monastery. It was not the end of the commune, though. Ahead, there were years of fruitful work in Rome, success in their home land of Germany, liberated from Napoleon. Only Overbeck, till the end of his days, remained unchanged in his adherence to Rome and to the traditional German costume that Karl Bryullov once found so funny.

The most famous work by a Nazarene is Overbeck’s painting Italy and Germany. One of the two ladies in the picture is Raphaelesque, the other Düreresque-looking. The colour of their hair, wreaths of dodder and laurel, styles of clothing — every single detail adds to the idea of the two different cultures' symbolic union. The picture was painted after the Nazarenes' ‘monastery period' was over, but the source it goes up to is Pforr’s diptych Sulamith and Maria (1811). The message of the latter is the same as that of Overbeck’s picture, and besides, it symbolises the friendship of the two founders of the Brotherhood. Back then, Overbeck started his own canvas as an answer and a match to Pforr’s, but left it unfinished after his friend’s death. Years later, Overbeck returned to the subject and created his picture, so much-celebrated now.

When: 1810 — June 1812

Notable residents: Johann Friedrich Overbeck, Franz Pforr, Johann Konrad Hottinger, Josef Wintergerst, Ludwig Vogel, Josef Sutter, Wilhelm von Schadow, Peter von Cornelius

More detail: In 1806, Napoleon in his victorious march through Europe, took control of all Germany. Confusion reigning everywhere, creative minds turned back to the past for ideals once lost. A group of German and Austrian artists, who admired Raphael, Michelangelo, Fra Angelico, Perugino, Dürer, Holbein, and Cranach, united in a community, settled in Italy, and started living a fairyland life.

In June 1810, the idealists set up an association similar to guilds of old, the Brotherhood of St. Luke (named after the apostle who was considered the patron of painters). After Overbeck was expelled from the Academy for ineptitude, the painters went to Rome, and there, from September 1810, lived in the monastery of Sant’Isidoro founded in the 16th century by Franciscan monks and deserted in the days of Napoleon. The friends were about twenty years old, and, with all the ardour of youth, they plunged into playing their good-old-time game. They wore German national costumes that used to be fashionable in older days, with berets, velvet doublets, collars of lace, capes, sometimes even swords — and the hairstyle alla nazarena (long hair parting in the middle) so as to look like Jesus of Nazareth. It is for that reason that they became known as the Nazarenes. By the way, it was the way Albrecht Dürer, whom they adored, used to wear his hair.

Within the commune, they referred to Overbeck as the Priest and Pforr as the Master. The Nazarenes were humble and pious. They only used cells as studios, never used corpses to study anatomy, never made sketches of nude women models, and sat for each other if there was a need of portraying a character in gorgeous garments. They refused worldly entertainments and social gatherings for work, prayers, walks, and evening debates in the refectory. In a purposely lofty manner, the Nazarenes expressed opinions on each other’s paintings, and discussed philosophy and literature. Their favourite book was Wilhelm Wackenroder’s Herzensergießungen eines kunstliebenden Klosterbruders (‘Outpourings of an Art-Loving Friar'). Following Pforr’s death by tuberculosis in 1812, the friends left the monastery. It was not the end of the commune, though. Ahead, there were years of fruitful work in Rome, success in their home land of Germany, liberated from Napoleon. Only Overbeck, till the end of his days, remained unchanged in his adherence to Rome and to the traditional German costume that Karl Bryullov once found so funny.

The most famous work by a Nazarene is Overbeck’s painting Italy and Germany. One of the two ladies in the picture is Raphaelesque, the other Düreresque-looking. The colour of their hair, wreaths of dodder and laurel, styles of clothing — every single detail adds to the idea of the two different cultures' symbolic union. The picture was painted after the Nazarenes' ‘monastery period' was over, but the source it goes up to is Pforr’s diptych Sulamith and Maria (1811). The message of the latter is the same as that of Overbeck’s picture, and besides, it symbolises the friendship of the two founders of the Brotherhood. Back then, Overbeck started his own canvas as an answer and a match to Pforr’s, but left it unfinished after his friend’s death. Years later, Overbeck returned to the subject and created his picture, so much-celebrated now.

Masterpieces created by the Nazarenes:

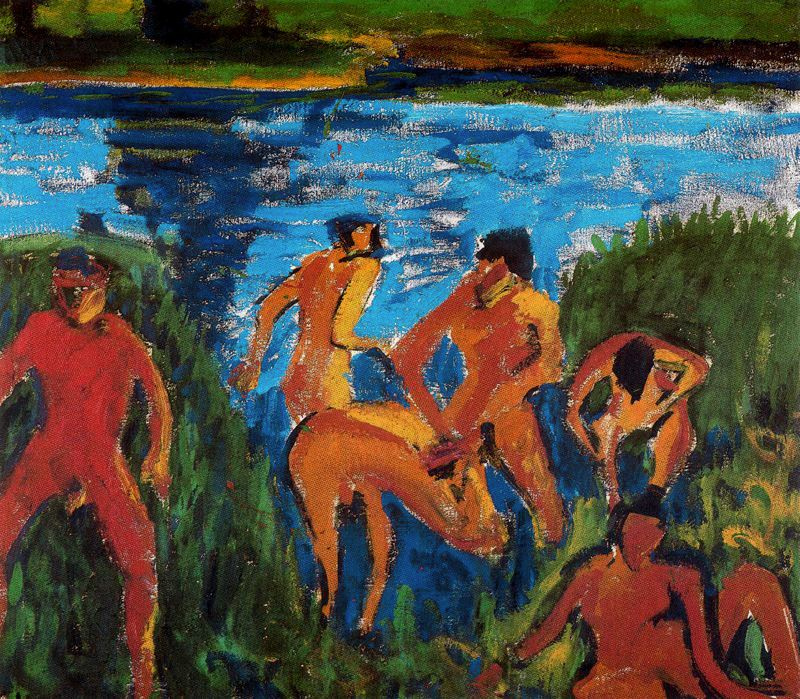

Bathers among the reeds

1909, 71×81 cm

Where: The Moritzburg lakes

When: 1905—1911

Notable residents: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Fritz Bleyl, Max Pechstein

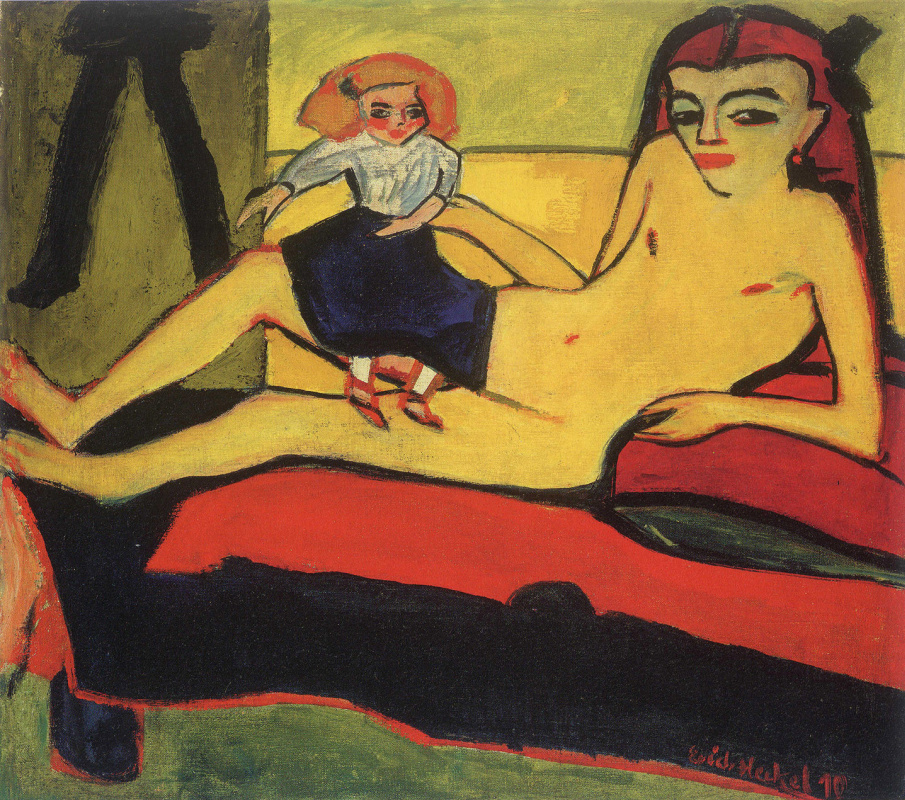

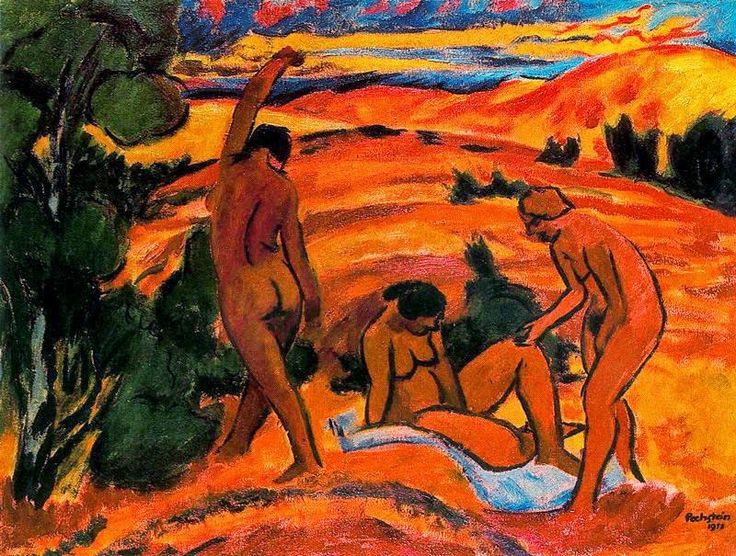

More detail: The idea of nudism must have been born in that very place — as an anti-urban and anti-industrial philosophy. For the artists of the Die Brücke group (the German for ‘bridge'), nature was more than just nature, and their models' nudity was a principle of their artistic manifesto. Formerly architecture students, now, aged 26 to 29, they were no longer young boys.

Every summer, the Die Brücke members stayed at the Moritzburg lakes, lived in the woods in an old brewery building, and spent all days going swimming, in the altogether, with their models. Then, back in Dresden, they prepared for winter exhibitions. New, non-traditional postures and foreshortenings of nude bodies, intentionally imperfect beauty, blatant indiscretion, no three-dimensionality effect (like in posters or prints), all these Expressionist discoveries were aimed at arousing the public’s primal, uncontrolled feeling of their real, though horrible, bestial descent. The Die Brücke members unfettered their own and watched other people’s bodies, thus trying to find their way of salvation.

Kirchner’s, Heckel’s, and Pechstein’s favourite model in those years was the nine-year-old girl Fränzi. Lina Franziska Fehrmann was the twelfth child in the family of a local needlewoman, an emigrant from Italy. The girl lived in a mean house near the railway station, and spent summers with the painters from Dresden — running, laughing, swimming, and basking in the sun. Her mother might have been acquainted to Kirchner’s mistress. That is how the Expressionists met their best and sincerest model, young, ignorant of taboos, and untainted by civilisation and social norms. Heckel would dilute the paints with water and solvent till they were rather watercolour paints than oils, Kirchner would lay thick, heavy layers of bright colours — to convey Fränzi's spontaneous body movements, sudden changes in the face, unrestricted energy.

Much later, when Kirchner had been back from the war and had some courses of treatment for his nervous breakdown, and Fränzi had two daughters and was working in the local print shop, the painter decided to call on Die Brücke's favourite. And she looked back on the years at the lakes as the happiest in her life.

The Die Brücke summer colony only existed for some years. In 1911, all of them, one by one, moved to Berlin. Later, they would be swamped with the terror of loneliness, with their own ambitions and opportunities, would be lost in concrete (or, perhaps, asphalt) jungle. Concrete jungle — this dismal idiom reflecting a pessimistic outlook appeared about the same time as the Expressionists' nudism.

When: 1905—1911

Notable residents: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Fritz Bleyl, Max Pechstein

More detail: The idea of nudism must have been born in that very place — as an anti-urban and anti-industrial philosophy. For the artists of the Die Brücke group (the German for ‘bridge'), nature was more than just nature, and their models' nudity was a principle of their artistic manifesto. Formerly architecture students, now, aged 26 to 29, they were no longer young boys.

Every summer, the Die Brücke members stayed at the Moritzburg lakes, lived in the woods in an old brewery building, and spent all days going swimming, in the altogether, with their models. Then, back in Dresden, they prepared for winter exhibitions. New, non-traditional postures and foreshortenings of nude bodies, intentionally imperfect beauty, blatant indiscretion, no three-dimensionality effect (like in posters or prints), all these Expressionist discoveries were aimed at arousing the public’s primal, uncontrolled feeling of their real, though horrible, bestial descent. The Die Brücke members unfettered their own and watched other people’s bodies, thus trying to find their way of salvation.

Kirchner’s, Heckel’s, and Pechstein’s favourite model in those years was the nine-year-old girl Fränzi. Lina Franziska Fehrmann was the twelfth child in the family of a local needlewoman, an emigrant from Italy. The girl lived in a mean house near the railway station, and spent summers with the painters from Dresden — running, laughing, swimming, and basking in the sun. Her mother might have been acquainted to Kirchner’s mistress. That is how the Expressionists met their best and sincerest model, young, ignorant of taboos, and untainted by civilisation and social norms. Heckel would dilute the paints with water and solvent till they were rather watercolour paints than oils, Kirchner would lay thick, heavy layers of bright colours — to convey Fränzi's spontaneous body movements, sudden changes in the face, unrestricted energy.

Much later, when Kirchner had been back from the war and had some courses of treatment for his nervous breakdown, and Fränzi had two daughters and was working in the local print shop, the painter decided to call on Die Brücke's favourite. And she looked back on the years at the lakes as the happiest in her life.

The Die Brücke summer colony only existed for some years. In 1911, all of them, one by one, moved to Berlin. Later, they would be swamped with the terror of loneliness, with their own ambitions and opportunities, would be lost in concrete (or, perhaps, asphalt) jungle. Concrete jungle — this dismal idiom reflecting a pessimistic outlook appeared about the same time as the Expressionists' nudism.

Masterpieces created at the Moritzburg lakes:

The dining-room at Brøndums Hotel, 1890s. In the frieze, there are portraits of artists who were, regularly or at times, involved in the life of the Skagen commune. On the walls, there are paintings the customers often donated to cover the cost of board and lodging. (Credit: artmarines.blogspot.com)

Where: Skagen, a fishing town

When: 1876 — the 1900s

Notable residents: Peder Krøyer, Marie Krøyer, Michael Ancher, Anna Ancher, Fritz Thaulow, Viggo Johansen, Christian Krohg, Oscar Björck

More detail: Cape Skagen is Denmark’s northernmost point. Here the North Sea meets the Baltic, and here the town of Skagen is located. At the end of the 19th century, it was not even a town, but a fishing village, with only one inn for travellers to stay. The painters Anna and Michael Ancher owned Brøndums Hotel and gathered their friends there.

When: 1876 — the 1900s

Notable residents: Peder Krøyer, Marie Krøyer, Michael Ancher, Anna Ancher, Fritz Thaulow, Viggo Johansen, Christian Krohg, Oscar Björck

More detail: Cape Skagen is Denmark’s northernmost point. Here the North Sea meets the Baltic, and here the town of Skagen is located. At the end of the 19th century, it was not even a town, but a fishing village, with only one inn for travellers to stay. The painters Anna and Michael Ancher owned Brøndums Hotel and gathered their friends there.

The hotel was Anna Brøndum's birthplace, and her family had owned the building for over a century: originally built as a farmhouse, later it was made a grocery shop and a guesthouse. Anna longed to paint, but women were not permitted to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. Nevertheless, she kept diligently copying illustrations from books, and then, a real artist appeared in Skagen. Michael Ancher was fascinated by its long beaches and deep northern light. First, he frequented Skagen alone, later accompanied by his friends. He gave Anna art lessons and in the end married her.

Marie and Peder Krøyer, on Michael’s invitation, also came to Skagen. There, the couple rented a house for the summer, strolled along the beaches, and in the evenings, had long conversations with the Anchers. It was Krøyer's idea to encourage their colleagues and friends to come there, paint en plein air during collective walks, go fishing — thus, from a distance, opposing the academic tradition (like everywhere in Europe, there was an opinion that the only decent way to artistic fame and recognition was the neo-Classical style and painting historical subjects). Some years later, the Krøyers would purchase and furnish their own house in Skagen, Brøndums would become the residence of the ‘Evening Academy', and students from Copenhagen would be sent there in summer for professional training.

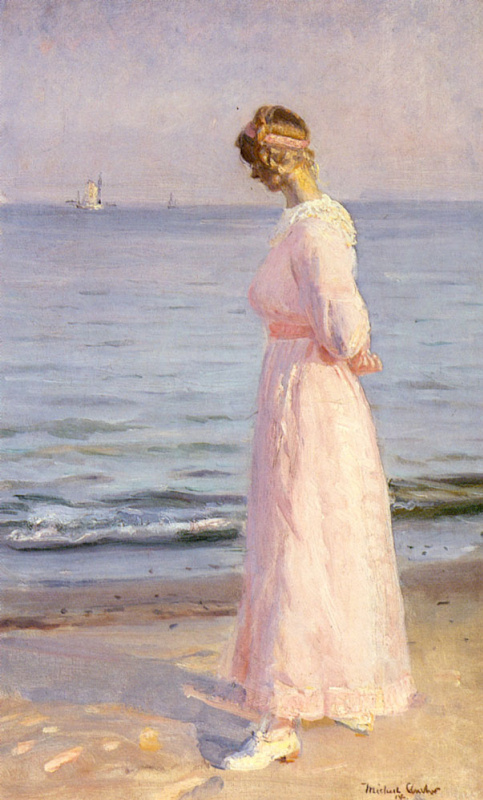

There, in Skagen, the revolution in northern art was going on slowly and without shots. Painters whose pictures art collectors often bought when the paints were still wet, and who were not reviled by critics from the capital, masterfully painted resonant plein air landscapes and intelligent women in white dresses — nearly at the same time as French Impressionists. The dream of living in a commune had French roots, too: a lot of those who would soon be called Northern enthusiasts from Skagen, once lived and studied in Paris where they watched, listened, and adopted the experience of hostels and of drunken debates about art. But they arranged everything in their own, different way: the harsh and windy province, and the complete absence of fashionable scandalous entertainments disposed for a peaceful revolution.

The Skagen inn became a museum when Krøyer and the Anchers were still alive, and the painters themselves appointed its board of directors. In the inn’s garden, a gallery was built, designed by a commune member and financed from private donations as well as from the governmental funds. It housed pictures taken directly from the studios.

Marie and Peder Krøyer, on Michael’s invitation, also came to Skagen. There, the couple rented a house for the summer, strolled along the beaches, and in the evenings, had long conversations with the Anchers. It was Krøyer's idea to encourage their colleagues and friends to come there, paint en plein air during collective walks, go fishing — thus, from a distance, opposing the academic tradition (like everywhere in Europe, there was an opinion that the only decent way to artistic fame and recognition was the neo-Classical style and painting historical subjects). Some years later, the Krøyers would purchase and furnish their own house in Skagen, Brøndums would become the residence of the ‘Evening Academy', and students from Copenhagen would be sent there in summer for professional training.

There, in Skagen, the revolution in northern art was going on slowly and without shots. Painters whose pictures art collectors often bought when the paints were still wet, and who were not reviled by critics from the capital, masterfully painted resonant plein air landscapes and intelligent women in white dresses — nearly at the same time as French Impressionists. The dream of living in a commune had French roots, too: a lot of those who would soon be called Northern enthusiasts from Skagen, once lived and studied in Paris where they watched, listened, and adopted the experience of hostels and of drunken debates about art. But they arranged everything in their own, different way: the harsh and windy province, and the complete absence of fashionable scandalous entertainments disposed for a peaceful revolution.

The Skagen inn became a museum when Krøyer and the Anchers were still alive, and the painters themselves appointed its board of directors. In the inn’s garden, a gallery was built, designed by a commune member and financed from private donations as well as from the governmental funds. It housed pictures taken directly from the studios.

Masterpieces created in Skagen:

Title illustration: Peder Severin Krøyer. Hip, Hip, Hurrah! People drinking champagne in the picture are the Danish artists from Skagen.

Text by: Anna Sidelnikova, Evgeniya Sidelnikova, Natalya Azarenko, Anna Vcherashnyaya, Olga Potekhina, Natalya Kandaurova

Text by: Anna Sidelnikova, Evgeniya Sidelnikova, Natalya Azarenko, Anna Vcherashnyaya, Olga Potekhina, Natalya Kandaurova